Korean War

On 28 October 1950, orders came from I Corps to saddle up the rest of the division and move north.

On 28 October 1950, orders came from I Corps to saddle up the rest of the division and move north. The Korean War seemed to be nearing a conclusion. The North Korean forces were being squeezed into a shrinking perimeter along the Yalu and the borders of Red China and Manchuria. By now, more than 135,000 Red troops had been captured and the North Korean Army was nearly destroyed.

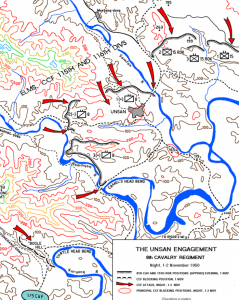

By 29 October, the 8th Cavalry Regiment along with elements of the 99th Field Artillery and “B” Company, 70th Tank Battalion had advanced north from Pyongyang to Sukchon, Sinanju and to the vicinity of Unsan, with the mission of relieving ROK elements of the I Corps in the area. Later that day, the 8th Cavalry received orders to attack all the way to the Yalu River.

Arrival at Yongsan-dong

On the morning of 30 October, the 5th Cavalry Regiment, under the command of Lieutenant Colonel. Harold K. Johnson, arrived at Yongsan-dong. The mission of the 5th Cavalry was to protect the rear of the 8th Cavalry, which had continued on north to Unsan where it was to relieve part of the ROK 1st Division. The 1st Battalion, 8th Cavalry, under the command of Major John Millikin, Jr., arrived at Unsan that afternoon. In conferring with KMAG (United States Army Advisory Group, Korea) officers attached to the ROK 12th Regiment, Millikin and his company commanders learned that the ROK line, about 8,000 yards north of Unsan, was under attack and being pushed back.

On 31 October, the 2nd and 3rd Battalions, 8th Cavalry, relieved the ROK 12th Regiment. But on the right an enemy attack during the night had driven back the ROK 2nd Battalion more than a mile. Its commander wanted his troops to regain the lost ground before they were relieved. Millikin’s 1st Battalion, however, moved into a defensive position behind the ROK 2nd Battalion line north of Unsan. That afternoon, General Milburn, US I Corps commander, visited the 8th Cavalry regimental command post and was advised that everything was all right.

By 1 November, the 8th Cavalry Regiment had advanced to within 50 miles of the Chinese border and the three battalions had moved up to relieve portions of the ROK 1st Division. The arrival of the US 8th Cavalry Regiment at Unsan had set in motion a redeployment of the ROK 1st Division. Upon being relieved west of Unsan, the ROK 11th Regiment had shifted southeast to establish contact with the ROK 8th Division on the corps boundary. The ROK 12th Regiment moved to a rest and reserve assembly area at Ipsok south of the Kuryong River, six air miles from Unsan. Still engaged in the battle at Unsan, the ROK 15th Regiment was desperately trying to hold its position across the Samt’an River east of the 8th Cavalry Regiment. In short, the US 8th Cavalry was to the north, west, and south of Unsan; the ROK 1st Division to the northeast, east, and southeast of it.

Later in the morning of 1 November, patrols from the 1st and 2nd Battalions, 8th Cavalry, clashed with Soldiers clearly identified as the Red Chinese CCF (Chinese Communist Forces). Contact with the CCF had begun increasing that afternoon, starting in the sector of the 1st Battalion, north of Unsan, then spreading west into the sector covered by the 2nd Battalion. By 1200 hours 1 November, the Chinese had cut and blocked the main road six air miles south of Unsan with sufficient strength to turn back two rifle companies which had been strongly supported by air strikes during daylight hours. The CCF had set the stage for an attack that night against the 8th Cavalry Regiment and the ROK 15th Regiment. The CCF attack north of Unsan had gained strength in the afternoon of 1 November against the ROK 15th Regiment on the east, and gradually it extended west into the zone of the 8th Cavalry Regiment. The first probing attacks there, accompanied by mortar barrages, came at 1700 hours against the right flank units, Companies “A” and “B”, 1st Battalion. There was also something new in the enemy fire support-rockets fired from trucks.

When Dusk Fell

When dusk fell that evening enemy Soldiers were on three sides of the 8th Cavalry – the north, west, and south. Only the ground to the east, held by the ROK 15th Regiment, was not in Chinese possession. As the battle grew, the attack of the CCF, well planned and executed in strength, broke through the ROK 15th Regiment. Following the issue of warning alerts of an impending withdrawal and armed with the most recent intelligence data, Colonel Holmes, Chief of Staff, 1st Cavalry Division, issued a final order for the 8th Cavalry Regiment to withdraw at 2400 hours. Soon afterwards, at about 0100 hours 2 November, the CCF cut the withdrawal route of the 1st and 2nd Battalion.

The 1st Battalion, 8th Cavalry had expanded its basic ammunition as well as the reserve which had been sent down from the regiment. “A” Company had engaged in “hand-to-hand” combat on both flanks. The 1st Battalion Commanding Officer, Major Millikin requested additional issues of ammunition. Receiving the division withdrawal order at midnight, with the 1st and 2nd Battalions, 8th Cavalry in heavy contact, the Regimental Commander, Colonel Palmer ordered a withdrawal to the south. The plan was for the 3rd Battalion to cover the withdrawal. Meanwhile, the 5th Cavalry, along with “A” Company, 70th Tank Battalion was ordered north to cover the planned withdrawal of the 8th Cavalry. In addition, the 7th Cavalry was called from Chinnampo to assist in the withdrawal.

The entire rear areas were swarming with the CCF. With heavy close-in fighting, the convoys of the 8th Cavalry RCP (Regimental Command Post) along with the 1st and 2nd Battalions managed withdraw under fire and to break through the CCF lines. Mostly, they were in scattered groups or individuals. Many of the groups were lost as well as critical equipment needed to support the withdrawal.

By 0200 hours, 2 November, the Chinese had blocked the last remaining road for a possible retreat overland. South of Unsan, the 3rd Battalion, commanded by Major Robert J. Ormond, had dug in just north of the Nammyon River. By dawn, the entire regiment was completely surrounded. The bulk of the 3rd Battalion was trapped by the Chinese. They formed into two islands of resistance. All day long fighter aircraft and bombers pounded the enemy positions. The battalion took heavy losses in its officers and enlisted men. The Commanding Officer, Major Ormond, was badly wounded and the staff were all wounded or missing in action.

The Troopers used the daylight respite gained from the air cover to dig an elaborate series of trenches and retrieve rations and ammunition from the vehicles that had escaped destruction. An L-5 plane flew over and dropped a mail bag of morphine and bandages. At dusk, a helicopter also appeared and hovered momentarily a few feet above the 3rd Battalion, intending to land and evacuate the more seriously wounded, but enemy fire hit it and it departed without landing. The battalion group was able to communicate with the pilot of a Mosquito plane overhead who said a relief column was on its way

The 1st and 2nd Battalions of the 5th Cavalry attempted a breakthrough from the south, but the CCF on “Eagle Hill” could not be overtaken. The 5th Cavalry, after receiving 350 casualties, pulled back.

Just after dark, a plane drops a message to the 3rd Battalion with orders that they are to begin an orderly withdrawal. The withdrawal route indicated was the only one possible – east from the road fork south of Unsan, across the Kuryong River, and then by the main supply route of the ROK 1st Division to Ipsok and Yongbyon. Major Millikin, 1st Battalion Commanding Officer, telephoned Colonel William Walton, 2nd Battalion Commanding Officer, that he would try to hold Unsan until the 2nd Battalion cleared the road junction south of it. Then he would withdraw. The 3rd Battalion, south of Unsan, was to bring up the regimental rear.

After examining all the options, the remaining men of the 3rd Battalion, decided to stand and fight even though they faced a full division of the CCF. The night brought a heavy bombardment of 120mm mortar fire and a mass attack of the CCF. Over a thousand enemy died outside the perimeter. With their own ammunition nearly spent, during the lull that followed, the men searched the battlefield around the perimeter to retrieve weapons and ammunition from the enemy dead.

3 November

On the morning of 3 November a three man patrol went to the former battalion command post dugout and discovered that during the night the Chinese had taken out some of the wounded. That day there was no air support. Remaining rations were given to the wounded. Enemy fire kept everyone under cover. The night of 3 November was a repetition of the preceding one, another barrage followed by a mass attack, with the Chinese working closer all the time. With their own ammunition was almost gone, after each enemy attack had been driven back, men would crawl out and retrieve weapons and ammunition from the enemy dead.

The morning of 4 November disclosed that there were about 200 men left able to fight. Casualties had risen to about 250 men. A discussion of the situation brought the decision that those still physically able to make the attempt should try to escape. The remaining forces of the battalion broke up into small groups and escape under the cover of darkness. Some were successful and many were not. Most of those men were either killed or captured that day, apparently in the vicinity of Yongbyon.

On 5 November, the Eighth Army announced that “as a result of an ambush” the 1st Cavalry Division would receive all the new replacements until further notice. In the next twelve days, The Eighth Army assigned 22 officers and 616 enlisted men as replacements to the 1st Cavalry Division. Nearly all of them went to the 8th Cavalry Regiment.

This event would be the most painful chapter in the proud history of the 1st Cavalry Division. At approximately 1600 hours on the afternoon of 6 November, the action of the 3rd Battalion, 8th Cavalry, as an organized force came to an end. It died gallantly. At first, more than 1,000 men of the 8th Cavalry Regiment were missing in action, but as the days passed, some of them returned to friendly lines along the Ch’ongch’on. Eventually the estimate was revised to a count of more than 600 officers and men were lost at Unsan, most of them from the 3rd Battalion.

Major Ormond

The heroic 3rd Battalion commander, Major Ormond, was among the wounded captured by the CCF in the perimeter beside the Kuryong. He subsequently died of his wounds and, according to some reports of surviving prisoners, was buried beside the road about five miles north of Unsan. Of his immediate staff, the battalion S-2 and S-4 also lost their lives in the Unsan action. About ten officers and somewhat less than 200 enlisted men of the 3rd Battalion escaped to rejoin the regiment. There were a few others who escaped later, some from captivity, and were given the status of recovered allied personnel.

Two weeks after the Unsan action, tank patrols were still bringing in men wounded at Unsan and fortunate enough to have been sheltered and cared for by friendly Koreans. On 22 November, the Chinese themselves, in a propaganda move, turned free 27 men who had been prisoners for two weeks or longer, 19 of them captured from the 8th Cavalry Regiment at Unsan.

For its actions, the 3rd Battalion was awarded a Republic of Korea Presidential Unit Citation and the Chryssoun Aristion Andrias (Bravery Gold Medal of Greece).

Note: Copied from https://www.first-team.us/tableaux/chapt_04/unsan.html by William H. Boudreau, Historian, 1st Cavalry Division Association