Gulf War

The Kuwait Theater of Operations

“The Security Council…noting that despite all efforts by the United Nations, Iraq refuses to comply with its obligation to implement resolution 660…In flagrant contempt of the Security Council…authorizes member states cooperating with the Government of Kuwait, unless Iraq on or before 15 January 1991 fully implements the foregoing resolutions, to use all necessary means to uphold and implement resolution 660 and all subsequent relevant resolutions and to restore international peace and security in the area.” – United Nations Resolution 678

Sun Tzu

In 205 B.C., Han Xin wanted to attack Wei Wangbao across the Yellow River. Han’s intention was to attack Wei from the rear at Anyi from faraway Xiayang. But he created a diversion by collecting materials for crossing the Yellow River at a nearby place called Linjing, as if he planned to cross the river there. Wei Wangbao was fooled and deployed his main force along Linjing, and left Anyi unguarded. Consequently, Han Xin’s troops crossed the river at Xiayang without resistance. This was one of the main campaigns between the Chu and Han states. – General Tao Hanzhang, Sun Tzu’s Art of War.

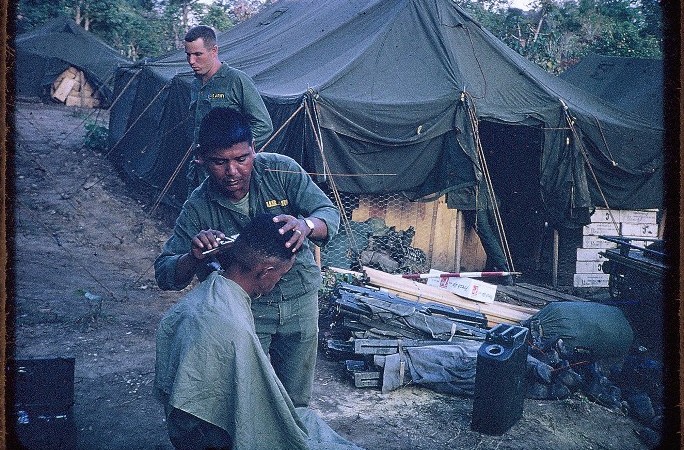

Just before 5:00 p.m. on February 5, 1991, enemy gunfire arced out from near a solitary border observation tower, missing a 1-7 Cav AH-1 Cobra flying reconnaissance. The pilot sent five 2.75 inch rockets into the area, scoring two direct hits. Two days later, another pilot watched as Soldiers entered the tower; he instantly radioed his discovery. Thirteen minutes later, a “Copperhead” laser guided round from a 1-82 Field Artillery 155mm howitzer slammed into the tower. Several enemy Soldiers bolted from it. They got as far as a nearby truck before disappearing in the explosion of a TOW missile streaking in from one of the Cobras. The unlucky sentinels were victims off the first use of Copperhead in combat. They were also among the first to feel the presence of General Schwarzkopf’s deception plan.

40 Divisions in the Kuwait Theater of Operations

With the air campaign in its third week, Allied intelligence still indicated the presence of over 40 divisions in the Kuwait Theater of Operations. Like Han Xin, Schwarzkopf decided to improve his odds by fooling the enemy. The 1st Cav, still guarding the assembling VII Corps to the south, was ordered to begin a deception in the Wadi al Batin. As 2nd Brigade Commander Colonel Randy House described it, the division would pull a “head fake,” drawing Hussein to focus his forces on the Wadi while the main attack gathered in the West.

The scheme played on Hussein’s own belief that Hafar al Batin and the Wadi would be the avenue of the Coalition’s main effort, the site of his “Mother of All Battles.” As Brigadier General Tilelli told his commanders, “It’s always easier to deceive an enemy into buying something they already believe is going to happen.”

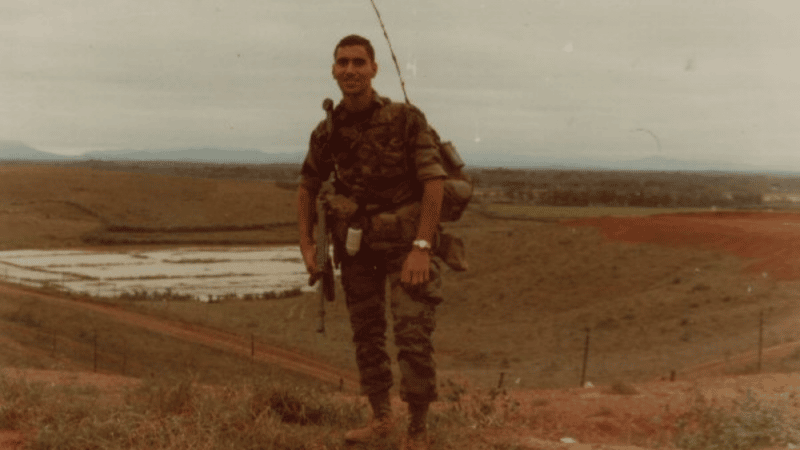

The division had by now crept north from the Tapline Road, well forward of any other U.S. division. Mere kilometers separated 1-7 Cav’s screenline from the border. To their front, at the border itself, isolated outposts from the division’s Long Range Surveillance Detachment watched for the enemy from sunken, invisible bunkers.

1-7 Cav’s Bradleys

Strung out on a line 70 kilometers long, 1-7 Cav’s Bradleys hunkered in fighting positions over a kilometer apart in the flat, featureless desert. Stretched to its limit, the squadron could not afford to offer its crews relief from the solitary vigil. It seemed like the top of the world – or the end of it. Only the disembodied voices of buddies and commanders on the radio, the low howl of a Bradley engine, the conversation of the crew, or the wind interrupted the quiet. Each day, the first sergeants arrived at the fighting positions with fuel trucks, chow and mail.

Squadron Executive Officer Major Mike Masterson was getting concerned about the continual operation of the squadron’s Bradleys without maintenance. At least his Cobra gunships, flying the screenline, but landing in the squadron’s rear, were examined by mechanics on a regular basis. He wasn’t sure how long the Bradleys – or the Soldiers – would be able to keep up. Masterson and squadron commander Lieutenant Colonel Walter “Skip” Sharp took to flying along the screenline in a scout helicopter “just to show them we were there and cared,” Masterson recalls. “As we passed over each Bradley, the crew would wave like crazy. Their morale was incredible.”

A healthy dose of stoic good humor helped. “My mother wrote me a letter, “ Private First Class Brian Hartner told a journalist visiting his Bradley. “She said that my cousin is over here and I ought to look him up; that it’d be real nice. He’s on the U.S.S. Missouri. It’s no sweat; I’ll just go over and look him up.”

As tough as it was for the unrelieved Soldiers on the Saudi frontier, it was proving tougher on the Iraqis facing them. The war overhead was flattening them. “It’s quiet, except at night. Then the A-10s and bombers take care of that,” one Soldier said. At night the airstrikes lit eerie domes of brilliant light on the northern horizon. A rapid series of subsequent blasts indicated something had been hit and was exploding, eliciting both winces and cheers from watching cavalrymen. The concussions followed, sweeping across miles of desert to buffet Soldiers watching awestruck from the screenline. The quiet ended simultaneously with the thump of distant explosions. That anyone could survive what came to be called “the Northern Lights” was beyond understanding.

Enemy Deserters

Within days of the air campaign’s opening, enemy deserters appeared on the empty horizon, walking south, some holding scraps of white cloth. None knew what lay before them; many expressed surprise at finding Americans. One said his commander had told the he would turn his back if any of his unit wished to leave. Others risked a bullet or retribution on their Family as they threaded their way through their own obstacle system to get away. By early February, deserters straggled in almost daily, arriving singly and in small groups – happy just to be alive. They were among the lucky few. In days, the 1st Cav would add its fire to the maelstrom consuming the enemy at the Wadi.

As the time for combat drew near, Division Artillery Commander Colonel James M. Gass had gathered his Soldiers in Alpha Battery, 21st Field Artillery, his battery of Multiple Launched Rocket Systems (MLRS), to talk to them about war. Gass, a combat Veteran, a brought these Soldiers to the desert and trained them, in the process earning their complete trust. Now he offered them his counsel and insight.

“Now, if you’ll let me pretend that I’m the coach and you’re the team, and we’re getting ready to play the Super Bowl – I’m talking about mental readiness – You have to prosecute violently, with great vigor and force to break the will of the enemy.”

Baptism by Fire

On February 13, against enemy artillery positions, the Soldiers experienced their baptism by fire. The Iraqis possessed a huge reservoir of artillery, boasting field pieces capable of ranges far greater than U.S. howitzers could manage. Virtually all could deliver chemical rounds. This made the destruction of Hussein’s artillery a high priority, while reinforcing the deception.

Captain Hamilton Hite waited for the go-ahead in his battery command post, wondering if this was going to be “it.” Hite, commander of Alpha Battery, 21st FA, had led his team through several false starts in the days following the division’s creep north into the Wadi. To Hite, however, this time looked real.

He was right. Just before dusk, he moved out in this Humvee, his ten tracked launchers in tow. Traveling approximately 20 kilometers they arrived at the final global positioning system initialization point, a gently sloping stretch of desert on the left shoulder of the Wadi. A deepening rose sky greeted each launcher as it pulled up to a fire direction sergeant to confirm its location and check its on-board positioning system. The dry air was electric – this mission had already gone farther than any of the previous attempts.

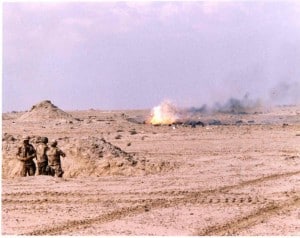

The word was “go.” Hite moved out in the gathering dark to the firing position, a wide flat area from which he could watch each launcher move into its pre-selected position and pivot left to face the last glow in the west. On ten launchers, ten box-like rocket pods, each containing 12 rockets tilted up and slowly swiveled right in unison, until all aimed north.

The Night Sky Burned Blue

The night sky burned blue as each launcher disgorged fire and steel. Rockets exploded from the pods in a thunderous “whoosh,” tracing a laser path skyward every three seconds. The battery emptied its pods in under a minute. Each rocket carried 644 bomblets, each capable of peppering 100 square meters. Seconds later, they exploded over eight Iraqi artillery units and an infantry company just settling into their evening routine.

The night sky burned blue as each launcher disgorged fire and steel. Rockets exploded from the pods in a thunderous “whoosh,” tracing a laser path skyward every three seconds. The battery emptied its pods in under a minute. Each rocket carried 644 bomblets, each capable of peppering 100 square meters. Seconds later, they exploded over eight Iraqi artillery units and an infantry company just settling into their evening routine.

Instantly, Hite ordered his battery out, a precaution against counter-battery fire. Engines screaming, the launchers pulled out of position, pods barely stowed. In single file, the battery sped to a rally point several kilometers back, and out of immediate danger. A supporting rocket battery from VII Corps was ready to attack any enemy artillery which might fire back, using target locations supplied by Alpha Battery, 333rd FA, with DIVARTY’s target acquisition radar. But this time there was no return fire. As Hite’s battery passed by, the supporting rockets loosed a volley on additional targets, providing his crews the spectacular view they had missed from within their shuttered cabs.

Evidence of Hite’s success, secondary explosions erupted in the target area long into the night. The war’s first MLRS raid was history.

Missions Came in Quick Succession

Now the missions came in quick succession. Intelligence indicated that Hussein had begun to focus on the Wadi. The deception went into full swing. The 8th Engineers went forward to blow holes in the border berm, making it look like the site of an attack. Their first mission, Berm Buster I, took place on the 14th. Covered by 1-7 Cav, the engineers moved up to the berm, blowing three lanes open with cratering charges and the 165mm cannon of their tank-like combat engineer vehicle. Later the same weapon destroyed three border observation towers near the berm.

Berm Buster II followed the next day. Just after 3:00 p.m. on the 15th, 3-82 FA pounded the area across the berm, destroying at least one observation post. Then Task Force 1-32 Armor moved up to secure the breach area, Abrams tanks from Alpha Company and Bradleys from Charlie Company. Even the battalion’s riflemen took up positions on the crest. Now the combat engineers dashed forward to the berm in their personnel carriers, dismounting to scramble up the 15-foot slope and place their charges. Thirty-five minutes later the explosions blew open nine lanes. The ruse was enhanced by the placement of dummy tanks and a loudly played record of vehicle noises. By 6:00 p.m., the mission was complete and the breach force gone. A surveillance team remained to watch for enemy reaction, but reported nothing.

That night, the division’s artillery, accompanied by the 42nd FA Brigade, attached from VII Corps, moved again into firing positions. In a massive raid called “Red Storm,” howitzers and rockets pounded 28 targets – enemy maneuver forces, artillery, and anti-aircraft sites. As Red Storm lifted, Apache attack helicopters from the 11th Aviation Brigade went in to finish the destruction. They passed low over Hite’s returning rocket launchers, ghostly shadows against the starry night.

Uproar in The Wadi

Over the next few days, the division continued its uproar in the Wadi, developing the deception and inflicting significant losses. Until the 16th, the division had suffered no combat losses, but at 10:30 a.m. that day, an M1A1 of Task Force 2-8 CAV struck a mine at the berm while the battalion was moving up. No one was injured. The tank was quickly recovered and repaired.

Occupying their new positions, 1st Brigade’s tank crews were forced to scrape three to four feet of sand at the berm’s crest to gain a clear view of the desert beyond. Wasting no time, the engineers blew three lanes into the berm and by the 18th, the Brigade had sent several mounted and dismounted recons into enemy territory. That afternoon, enemy artillery hit a TF 2-8 Cav foray. They withdrew through the lanes without loss. In moments, USAF A-10 airstrikes silenced the artillery.

The engineer CEVs did more than blow up dirt berms. One leveled an Iraqi border check point suspected of controlling sporadic artillery strikes in the 1st Brigade area. From near the CEV, 2nd Lieutenant Kenneth Cary, an Abrams platoon leader in Alpha Company, TF 2-8 Cav, watched as the first 165mm round struck the building harmlessly. “It was a dud. And then this black cat came tearing out. The next round blew down the entire wall.”

Early on the 19th, TF 2-8 Cav moved out on a recon, returning after destroying an enemy ammo cache. That evening 2nd Lieutenant Rick Davis, leading a platoon of TF 2-8 Cav M1A1s, reported enemy vehicles and Soldiers moving to his front. 1-82 FA pumped illumination rounds over the area. After waiting nearly an hour for confirmation that they were hostile, Davis was ordered to engage. His tanks opened fire, hitting one vehicle. Task Force 2-5 Cav’s Bradleys joined in, hitting an Iraqi MTLB ammunition carrier with a TOW missile as TF 2-8 Cav mortar fire pelted the dismounts. The next morning, infantry swept the area, capturing several enemy survivors.

Scuds

The torrent of alerts has slackened since January. While the reports of Scuds hitting Dhahran, Riyadh, and Tel Aviv caused concern, those were distant places. As long as Hussein was flinging only high explosives and not chemicals, the admittedly tragic hits on cities had little effect on life on the frontier. That changed on Valentine’s Day. While Soldiers of TF 1-32 Armor were at the division’s shower point in Hafar al Batin, luxuriating in the first shower many had taken in weeks, a Scud slammed into an auto parts store across the street, one of two fired into the area. The explosion tore the building apart and sent Soldiers flying for cover. But the siren call of running water proved irresistible, and the grimy Soldiers soon resumed their hard-won showers.

Over the next few days, DIVARTY continued to hit high payoff targets – maneuver units, artillery, anti-aircraft, and command posts – with shells and rockets. Watching the almost nightly displays of pyrotechnics was the evening’s entertainment among units in the Wadi area.

At the main command post, Soldiers gathered on the perimeter berm, applauding the strikes as though they were watching their favorite ball team putting the visitors away. Essentially, they were.

On the 15th, Iraq’s Revolutionary Council tried to slow the Allied pace. Baghdad offered to pull out of Kuwait after a cessation of all operations against Iraq. President Bush called it a “cruel hoax.” Lieutenant General Franks, commanding VII Corps, to which the 1st Cav was still attached, ordered all operations to continue. His corps was now nearly in position to the west of Hafar al Batin.

Prisoners Continued to Dribble In

Prisoners continued to dribble into the division’s lines, primarily 1-7 Cav’s positions. They were questioned initially by a team located with the squadron. Willing to talk, they provided invaluable intelligence, confirming that Hussein was thickening his forces at the Wadi. At least four divisions faced the 1st Cav, all smarting from the strikes hurled out since early February,

The Iraqis had bitten; it was time to set the hook. On the 19th, Colonel Randy House was ordered to conduct a reconnaissance in force across the border the next day to “determine enemy locations, composition, strength, and intent.” Stealth wasn’t a priority; House was instructed to elicit an enemy response, but not get mired in decisive combat. As darkness fell on the 19th, a company of Task Force 1-5 Cav reconned the crossing sites on the berm and probed three kilometers beyond. It returned, having found nothing. At noon on the next day, Knight Strike I, named for the 1-5 Cav “Black Knights,” kicked off.

Task Force 1-5 Cav moved north in a diamond, the Scout Platoon’s cavalry fighting vehicles on point, followed closely by Alpha Company’s Bradleys, leading and centered, Bravo Company’s tanks on the left, Delta Company’s on the right, and Charlie Company’s Bradleys trailing. Tucked into the formation were the task force’s two platoons of 8th Engineers and its Vulcans and Stinger teams from 4th Battalion, 5th Air Defense Artillery. The brigade’s field artillery remained at the berm, where it could fire 536 rounds in support of Blackjack. House accompanied the task force in his command vehicle.

Task Force 1-5 Cav moved on. About 10 kilometers past the berm, Alpha Company made contact. The Bradleys instantly laid a base of fire while the tank companies raced up. The task force struck savagely, destroying an enemy battalion in minutes. USAF A-10s swept away over 100 Iraqi artillery pieces entrenched and invisible from the ground. The task force started taking prisoners.

Knight Strike

Then Knight Strike turned ugly. The rounds struck while the Scouts and Alpha Company were collecting prisoners. Suddenly artillery was falling on the engineers and Alpha Company was taking direct fire. “All of a sudden, I’m about a thousand meters back…observing with my binoculars from my command track…and the Vulcan that’s behind me takes a hit. I can hear, and then I can see, rounds going through my antennas,” House recalled. In quick succession, enemy direct fire hit two Alpha Company Bradleys. “I was neck-high out of the hatch [of my Bradley] scanning for a new target when the noise and pressure wave from the X.O’s vehicle [the Bradley of the Alpha company executive officer, 1st Lieutenant Christopher Robinson] getting hit caused me to look back to my left rear. I saw smoke and flame coming off his turret and burning pieces going everywhere,” wrote Staff Sergeant Christopher Cichon after the battle. Moments after seeing Robinson’s Bradley struck, Cichon, dismounted, watched his own take a hit.

The Scouts took fire, too. House watched the Scout platoon leader in action. “I could see his track getting the s— shot out of it and he was talking like he was at the beach. He says, ‘Taking fire, returning same.’” TF 1-5 Cav’s tanks quickly regained firepower superiority while Charlie Company moved up to help with the prisoners. Shortly before 2:00 p.m., an artillery smoke screen covered the task force’s withdrawal, ordered by Brigadier General Tilelli. That night, and for the next four days ending in the start of the ground offensive, heavy air strikes pounded the Wadi.

On the 24th, hours after General Schwarzkopf launched his “Hail Mary” attack, House was ordered back up the Wadi. The Allied offensive was meeting with unanticipated success; the enemy defense was fast disintegrating and Schwarzkopf needed the enemy forces in the Wadi held down.

Blackjack moved out at approximately 5:00 p.m. House was to move north in a limited attack to fix the enemy’s focus on the Wadi. He was also to feel for soft spots through which the division could charge north, thus avoiding the longer route taken by VII Corps. The division was now Theater reserve, subject to be recalled if needed. Consequently, House was directed to be careful and preserve his forces.

Night fell as rain and sand whipped the advancing armor of the brigade’s desert wedge. House recalled running into enemy defenses soon after nightfall. Calling on A-10s and artillery, adjusted by the division’s OH-58D laser designator-equipped helicopters, Blackjack fought to the enemy’s fire trenches. The oil-filled slits, hundreds of meters long, blocked progress up the Wadi. Emplaced in two staggered ranks so that they overlapped, the only way through burning trenches was around the edges, and into enemy kill sacks. Lit as Blackjack approached, they burned convulsively in the wind. Clouds of acrid oil smoke and flying sand reduced visibility to the front of one’s tank. The brigade came on and they did, the enemy fought back. “All night long, moving firing…getting through minefields, marking those minefields, getting unit through, and right before light the next morning…the Apaches struck at bunkers and enemy in and amongst the fire trenches and on the flanks of the brigade. Now House attacked straight at the fire trenches, pulsing strips of towering flame and smoke vivid against the grey dawn before him. Artillery pounded the defenders; Copperhead rounds destroyed four tanks and a ZSU 23-4 anti-aircraft gun. Apaches came in low, forming in battle lines, engaging with 30mm cannon and Hellfire missiles. One took a hit from an anti-tank gun and went down, its crew whisked out under fire, clinging to a rescuing Apache’s wings.

The enemy stiffened, refusing to yield. House knew he could not pierce the trenches, but there was no soft spot; it would take time and losses to open a route for the division. At about noon on the 25th, Tilelli ordered the brigade back. The main attack in the west was going better than expected; the Iraqis had been diverted with results beyond all expectations. The deception had destroyed elements of the Iraqi 12th Armored Division, 25th, 27th, 28th, 31st and 47th Infantry Divisions, and a Corps artillery group. The enemy had focused on the Wadi, weakening his flanks, and missing entirely the movement of VII Corps. There no longer was any need to slug it out in the Wadi al Batin.

In the rain, Blackjack returned to Saudi Arabia, refueled and prepared with the rest of the 1st Cav to launch into the final assault.

Excerpted from America’s First Team in the Gulf by Jeffrey E. Phillips and Robyn M. Gregory, Taylor Publishing Company, Dallas, Texas.