5th Cavalry Regiment

Information compiled and composed by William H. Boudreau

On 3 March 1855, the 5th Cavalry Regiment, originally designated as the 2nd Cavalry, was activated in Louisville, Kentucky with troops drawn from Alabama, Maryland, Missouri, Indiana, Kentucky, Pennsylvania, Ohio and Virginia.

The regiment soon became a crack outfit with some of the best horsemen and Soldiers in the mounted service. Each company rode mounts of one color; a colorful sight during regimental dress parades. Company “A” rode grays; Company “B” and “E” rode sorrels; Company “C”, “D”, “F” and “I” had bays; Company “G” and “H” rode browns and Company “K” rode roans.

On 27 September 1855, after training at Jefferson Barracks, Missouri, the Regiment, under the command of Colonel Albert Sydney Johnston, received orders to ride southwest to Fort Belknap, Texas. The line of march of the 700 men with 800 horses carried them through the Ozark Mountains of Missouri, through Arkansas and into Indian Territory. The long hard march of the regiment depended on the resources of the surrounding country for meat, flour and forage. On 27 December, the entire regiment arrived at the post during a severe blizzard. The temperature dropped below zero, ice froze six inches thick and horses on the unprotected picket line died from the extreme exposure. Established in 1851, Fort Balknap was one of the largest posts in North Texas prior to the Civil War. It was built to protect early settlers, travelers moving on west and was a stop on famous Butterfield Overland Mail Route.

Upon arrival at Fort Belknap, Colonel Johnston received orders to set up Headquarters along with Companies “B”, “C”, “D”, “G”, “H” and “I” at Fort Mason, Texas. On 2 January 1856, Johnston’s group negotiated the icy waters of Clear Fork, the Pecan, the Colorado and the San Saba Rivers in their journey to Fort Mason. On 14 January, they arrived at their assigned station which had been abandoned for nearly two years. The Troopers were soon put to work repairing old buildings and constructing new ones. By late spring, a new Fort Mason flourished atop Post Hill. On 22 February 1956, Company “C” of the 2nd Cavalry, under the command of Captain James Oaks, engaged the Waco Indians in their first battle just west of Fort Terrett.

In July 1857, Lt. Colonel Robert E. Lee arrived at Fort Mason to take command of the 2nd Cavalry Regiment. In the same month, Lt. John Bell Hood led his company of the 2nd Cavalry on a dramatic foray in Texas. Spotting a band of Indian Warriors, Hood moved ahead to parley, stopping nearly 30 yards from five Indians who were holding a white flag of truce. At this point, the Indians dropped their flag of truce and set fire to rubbish which they had previously collected to provide a smoke screen. Thirty Indians, hiding within 10 paces of the troops, began an attack on their flank with arrows and firearms. The Troopers charged and a hand to hand battle ensued. Outnumbered two to one, the Troopers withdrew, covering their retreat with revolver fire. Wounded in this action, Lt. Hood recovered and continued serving in the Regiment.

For the next four years of service in the southwest, the regiment fought some 40 engagements against the Apaches, Bannocks, Cheyennes, Comanches, Kiowas, Utes and other fierce tribes along with the Mexican bandits. The old frontier policy of passive defense against the Indian aggression was quickly abandoned as the regiment rode patrols, pursued and attacked. On 15 February 1858, Major Hardee was instructed to proceed from Fort Belknap with Company “A”, “F”, “H” & “K” to Otter Creek, Texas and establish a Supply Station. On 29 February, they came upon a large encampment of Comanche Indians near Wichita Village. On 1 October, the troops made a charge against the Indians and after a two hour hand to hand fighting, the enemy was routed in the greatest single defeat inflicted against the Comanches.

The outbreak of the Civil war in 1861 added an ironic, but important footnote to the history of the 2nd Cavalry Regiment. Twelve officers of its original staff returned to their birthplace to eventually become generals in the Confederate Army. The namesake of Fort Hood, “John Bell Hood”, a second lieutenant rose to become a famous Confederate General, commanding the Texas Brigade. The most famous, the regiment’s second commanding officer, Lt. Colonel Robert E. Lee rose to become commander of the entire Confederate Army. As the United States dissolved into the Confederacy and Union in 1861, the 54 year old Robert E. Lee returned to the East and was offered the opportunity to take command of the Union Army, but he declined because of his wife’s illness. On 20 April 1861, Lee resigned from the US Army and accepted command of the Army of Virginia.

Arriving at their destination of Carlisle Barracks, Pennsylvania, the 2nd Cavalry Regiment was rebuilt with new officers and recruits and, as was the 1st Cavalry Regiment, was assigned to the Union “Army of the Potomac” that was organized under General George McClellen. The regiment fought its first battle of the Civil War and its last designated as the 2nd Cavalry Regiment, at the first Battle of Bull Run (1st Manassas) on 21 July 1861. By an act of congress dated 3 August 1861 and a general order dated 10 August 1861, the 2nd US Cavalry Regiment was redesignated as the 5th US Cavalry Regiment.

During the Civil War the regiment fought valiant battles at Gaines Mills, Fairfax Courthouse, Falling Waters, Martinsburg, the Wilderness, Shenandoah Valley and numerous others. In the end, superior manpower and supplies of the Union won out. On 27 June 1862, the most memorable feat of the regiment came at Gaines Mill when they charged a Confederate Division commanded by a former comrade in arms, General John Bell Hood. This charge against a numerically superior force stopped Hood’s division and saved the artillery of the Army of the Potomac from capture. On 9 April 1865, Troopers of the 5th Cavalry sat astride their horses as an honor guard at Appomattox, Virginia as their former commander, General Lee, surrendered to end the Civil war.

In September 1868, the regiment received orders to prepare for duty against hostile Indians in Kansas and Nebraska. In the following years the 5th fought many skirmishes and battles with the Sioux, Cheyenne, Arapaho and Apache Indians. After General Custer and 264 of his men died at Little Big Horn, Troopers of the 5th Cavalry rode after the Sioux to avenge their deaths. In the next few years the principal engagements in which the regiment took part were with the 2nd and 3rd Cavalry were the prolonged Big Horn and Yellowstone Expeditions.

As the Indian actions continued, a member of the 5th Regiment, Lieutenant Adolphus Washington Greely who had headed the construction of some 2,000 miles of telegraph lines in Texas, Montana and the Dakota Territories, was named to lead an expedition to the Arctic. On 7 July 1881, Greely and his men left St. John’s Newfoundland and arrived at Lady Franklin Bay on 26 August, to establish Fort Conger on Ellesmere Island, Canada, just across the narrow strait from the northwest tip of Greenland. They explored regions closer to the North Pole than men had previously gone. Although they were able to gather much needed scientific data about arctic weather conditions which was used by later arctic explorers, the expedition lost 18 out of the original 25 members of the party through starvation because a supply ship was unable to break through the heavy iced seas.

In 1898, the regiment traveled from San Antonio to the embarkation port of Tampa, Florida to enter the Spanish American War. The 5th Cavalry finally got into fighting in a new setting 2,000 miles from their home ranges. More than 17,000 troops, including the 5th Cavalry, landed at the southwest coast of Puerto Rico at the small port of Guancia 15 miles west of Ponce. In July 1898, the regiment was split into four columns of infantry and cavalry and in early August began fanning out across the mountainous countryside.

Troop “A” of the 5th Cavalry Regiment saw much of the action. It was part of a 2,800 man force (the Independent Regular Brigade) sent north under the command of General Theodore Schwan. Troop “A” performed well at the short battles at Las Marias and Hormigueros where the 1,400 Spanish defenders resisted briefly before a hasty retreat. By these victories, the 5th Cavalry earned the right to display the Maltese Cross at the top of its regimental shield. The Spanish turned over the island of Puerto Rico to the United States on 10 December 1898. The 5th Cavalry remained on the island until early in 1899, when it returned to San Antonio.

In 1901, the regiment, less the 2nd Squadron, sailed to the distant Philippine Islands to help put down the bloody insurrection. In 1902, the 2nd Squadron proceeded to the Philippines to join the main body of the regiment. Dismounted, they battled in the jungles of the Pacific to end the Moro Insurrection. In March 1903, back in the United States, Troopers of the 5th Regiment found themselves spread throughout Arizona, Colorado, New Mexico and Utah. Some of them fought Navaho Indians in small rebellious battles located in Arizona and Utah. The regiment remained fragmented for 5 years. In January 1909, Headquarters and the 1st and 3rd Squadrons were reassigned to Pacific duty strengthening the US military presence in the new territory of Hawaii. Although there was a small Army population on Oahu, the first deployment of cavalry troops provided the need to start a permanent Army post. By December, Captain Joseph C. Castner had drawn up the plans for the development of today’s Schofield Barracks. The 2nd Squadron arrived in October 1910, to help in the completion of the construction.

In 1913, border threats to the United States brought the regiment back to the deserts of the Southwest, stationed at Fort Apache and Fort Huachuca, Arizona. In 1916, the regiment was dispatched to the Mexican border to serve as part of the Mexican Punitive Expedition. Under “BlackJack” Pershing, the 5th Cavalry Regiment crossed the Rio Grande into Mexico and was successful in stopping the border raids conducted by bandits of Pancho Villa who had expanded their operations of rustling cattle, robbing banks and killing into the United States. The regiment remained with the Punitive Expedition in Mexico, until 5 February 1917. After several relocations, in October, the regiment moved into Fort Bliss, relieving the 8th Cavalry Regiment.

In 1918, airplanes and tanks had emerged from World War I as the glamour weapons of the future. By contrast, the long history of the Cavalry was not finished. The cavalry remained as the fastest and most effective force for patrolling the remote desert areas of the Southwest and Mexican boarders. Airplanes and mechanized vehicles were not reliable enough or adapted for ranging across the rugged countryside, setting up ambushes, conducting stealthy reconnaissance missions and engaging in fast moving skirmishes with minimal support. In many ways, it was just the beginning of a new era. The cavalry was about to be transformed and revitalized – by the activation of the 1st Cavalry Division

The regiments that were soon to become part of the 1st Cavalry Division were far from idle. Troopers were getting into frequent, small scaled combats with raiders, smugglers and Mexican Revolutionaries along the Rio Grande River. In one skirmish in June 1919, four units, the 5th and 7th Cavalry Regiments, the 8th Engineers (Mounted) and 82nd Field Artillery Battalion (Horse) saw action against Pancho Villa’s Villistas. On 15 June, Mexican snipers fired across the Rio Grande and killed a Trooper of the 82nd Field Artillery who was standing picket duty. In hot pursuit, the Troopers and the horse artillery engaged a column of Villistas near Juarez. Following a successful engagement, the cavalry expedition returned to the United States side of the border.

On 13 September 1921, with the initiation of the National Defense Act, the 1st Cavalry Division was formally activated at Fort Bliss, Texas. The first unit of the 1st Cavalry Division, the famous 1st Cavalry Regiment, had been preassigned to the 1st Division on 20 August 1921, nearly a month before the formal divisional activation date. Upon formal activation, the 7th, 8th and 10th Cavalry Regiments were assigned to the new division. Other units initially assigned to the 1st Cavalry Division in 1921, included 82nd Field Artillery Battalion (Horse), the 13th Signal Troop, the 27th Ordnance Company, Division Headquarters and the 1st Cavalry Quartermaster train which later became the 15th Replacement Company. Major General Robert Lee Howze was assigned as the 1st Cavalry Division commander. It was not until 18 December 1922, when the 5th Cavalry Regiment was assigned, relieving the 10th Cavalry Regiment.

In 1923, the 1st Cavalry Division assembled to stage its divisional maneuvers at Camp Marfa, Texas. The 5th Cavalry Regiment participated in the maneuvers and the line of march for the unit was: Fabens, Fort Hancock, Finley Sierra Blanca, Hot Wells, Lobo Flats and Valentine. The wagon trains, all drawn by four mules (no motorized vehicles yet), were endless. Over the next four years, elements of the division were stationed at Camp Marfa, Fort Bliss and Fort Clark, which were all in Texas. The early missions of the division and the 5th Cavalry were largely a saga of rough riding, patrolling the Mexican border and constant training. Operating from horseback, the cavalry was the only force capable of piercing the harsh terrain of the desert to halt the band of smugglers that operated along the desolate Mexican border.

The depression of the 1930’s forced thousands of unemployed workers into the streets. From 1933 to 1936, the 3,300 Troopers of the 1st Cavalry Division provided training and leadership for 62,500 people of the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) in Arizona-New Mexico District. One of these workers significant accomplishments was the construction of barracks for 20,000 anti-aircraft troops at Fort Bliss, Texas. When World War II broke out, many of those who had been in the CCC were well prepared for the rigors of military training.

The entire Army was expanding and acquiring new equipment. Faster and lighter medium tanks were assigned to both, cavalry and infantry units. The mobile 105mm howitzer became the chief artillery piece of the Army Divisions. There was also a new urgency being expressed by Washington. Japan, which had invaded Manchuria in 1931, continued to expand conquests into China and Nazi Germany had annexed Austria and was threatening to seize Czechoslovakia. In 1938, against the background of international tensions, the 5th Cavalry Regiment joined in with the 1st Cavalry Division at its second divisional maneuvers in the mountains near Balmorhea, Texas. New units, including the 1st Signal Corps, the 27th Ordnance Company and the 1st Medical Squadron joined the 1st Cavalry Division.

The staging of the third divisional maneuvers near Balmorhea, Texas was made even more memorable and intense by their timing. The starting of the maneuvers, 01 September 1939, coincided with the invasion of Poland by Germany, who used the most modern and deadly military force of its time. Failing to influence Hitler of the grave consequences of his actions, both Great Britain and France initiated a declaration of war on 3 September 1939.

Having returned to Fort Bliss from the 3rd Army Louisiana readiness maneuvers in October 1941, the 5th Cavalry Regiment was trained and ready for action. Isolationist politics was still strong in Congress. Major priorities were placed on building up the industrial capacity to supply equipment to the Allies in Europe. Many officers and men took leave or returned to civilian life. Other, more dedicated, members of the 1st Cavalry Division began to prepare for battle. They had no way of knowing that their first combat engagement would not be for more than two and a half years.

On 7 December 1941, without warning, the Japanese destroyed the American fleet at Pearl Harbor. Although the 1st Cavalry Division was created as a result of a proven need for large horse-mounted formations, by 1940 many thought that the march of progress had left the horse far behind. All doubt was erased with the surprise of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. Immediately Troopers returned to the 1st Cavalry Division from all over the United States. They outfitted their horses and readied their weapons and vehicles in anticipation of the fight against the Axis.

In February 1943, the entire 1st Cavalry Division was alerted for an overseas assignment. An impatient 1st Cavalry Division was dismounted and they were processed for movement to the Southwest Pacific theater as foot Soldiers. In mid June 1943, the last troops of the division departed Fort Bliss, Texas for Camp Stoneman, California and later on 3 July, boarded the “SS Monterey” and the “SS George Washington” for Australia and the Southwest Pacific.

On 26 July, three weeks later, the division arrived at Brisbane and began a fifteen mile trip to their new temporary home, Camp Strathpine, Queensland, Australia. The division received six months of intense combat jungle warfare training at Camp Strathpine in the wilds of scenic Queensland and amphibious training at nearby Moreton Bay. In January 1944 the division was ordered to leave Australia and sail to Oro Bay, New Guinea. After a period of staging in New Guinea, it was time for the 1st Cavalry Division to receive their first baptism of fire.

On 27 February, Task Force “Brewer”, consisting of 1,026 Troopers, embarked from Cape Sudest, Oro Bay, New Guinea under the command of Brigadier General William C. Chase. Their destination was a remote, Japanese occupied island of the Admiralties, Los Negros, where they were to make a reconnaissance of force and if feasible, capture Momote Airdrome and secure a beachhead for the reinforcements that would follow.

Just after 0800 on 29 February, the 1st Cavalry Troopers climbed down the nets of the APD’s and into the LCM’s and LCPR’s, the flat bottomed landing craft of the Navy. The landing at Hayane Harbor took the Japanese by surprise. The first three waves of the assault troops from the 2nd Squadron, 5th Regiment reached the beach virtually unscathed. The fourth wave was less lucky. By then, the Japanese had been able to readjust their guns to fire lower and some casualties were suffered.

Troops under the command of Lt. Col. William E. Lobit of Galveston, Texas, fanned out and attacked through the rain. They quickly fought their way to the Momote airfield and had the entire facility quickly under control in less than two hours. The United Press would hail the Los Negros landing as “one of the most brilliant maneuvers of the war.” The Associated Press would call it “a masterful strategic stroke.”

Shortly after 1400 on “D” day, General MacArthur inspected and praised the Cavalry troops actions and accomplishments; then ordered General Chase to defend the airstrip at all costs against Japanese counterattacks. He finally headed back to the beach where he presented the Distinguished Service Cross to Lt. Marvin J. Henshaw, 5th Cavalry, of Haskell, Texas. Lt. Henshaw had been the first American to land on Los Negros in the first wave, leading his platoon ashore through the narrow ramp of a Higgens boat.

Nightfall was coming which, as it was known, would bring a nighttime counterattack from the enemy. Early in the morning, around 0200, the enemy came back in force. In the darkness the Japanese had made it into the 5th Cavalry’s perimeter. Hand to hand fighting broke out near some foxholes. Tough fighting raged the next day and through the night. Japanese pressure on the invasion force remained desperate and intense. The music of the old cavalry charge could almost be heard when the rest of the 5th Cavalry reinforcements was riding toward the beach in LST,s and other landing craft. In a coordinated action, the 40th Naval Construction Battalion (Seabees) landed on Los Negros Island in support of the 5th Cavalry. Their mission was to reconstruct the Momote Airfield. Assigned to defend a large portion of the right flank, the 40th suffered heavy casualties while defending the airfield with the horseless Soldiers of the 5th. Along with the 40th, the consolidated 5th Regiment soon secured the entire Momote airfield and spent the long night of 2 March, repulsing suicidal attacks, especially against the north and northwest sectors of the perimeter.

The third day on Los Negros, 3 March, was a red letter day for the 1st Cavalry Division. It was the 89th anniversary of the founding of the 5th Regiment. There was little time for celebration; the fresh well equipped Imperial Marines were counterattacking and the worst was yet to come. Combat raged through the night of 3 March and the morning of 4 March. At one point the Japanese had penetrated several hundred yards inside the defense parameter near “G” Troop. The cavalrymen rallied and they wiped out the attackers. It was during the fierce night fighting that a member of “G” Troop, 5th Cavalry, won the division’s first Medal of Honor. Staff Sergeant Troy A. McGill, of Ada, Oklahoma was in charge of a defensive position of foxholes dug into a revetment about 35 yards in front of the main line of resistance. Suddenly Sgt. McGill and his men found themselves in the center of a swarming, drink crazed Banzai attack by 200 Japanese Soldiers. All but one of McGill’s men were killed or wounded. McGill ordered the survivor to drop back, and gave him covering fire. When his weapon failed, McGill charged the enemy and clubbed as many as he could before he was killed. The next morning, 146 enemy dead were found in front of his position.

More reinforcements arrived shortly before noon of 4 March, and quickly went into action. The 2nd Squadron, 7th Cavalry relieved the 5th Cavalry who had been in continuous combat for four days and nights. On 6 March, the 5th Cavalry went back into action to occupy Porolka and the first American airplane landed on the Momote airstrip which had been repaired by the Seabees. The next day the 5th pushed south and overran Papitalai Village after a short amphibious landing assault. By 10 – 11 March, mop up operations were underway all over the northern half of Los Negros Island and attention was being given to a much bigger objective immediately to the west; Manus Island.

By 16 March 1944, Momote airstrip was in use and the airdrome well on its way to completion. The airstrip was quickly repaired so that by 18 May, fighters could operate from it. Momote Airdrome was surfaced with coral and equipped with taxiways, hard stands, and storage areas. By the end of the campaign over 7,000 barrels of bulk petroleum fuel were stored at Momote for operations. Also, a causeway was built spanning a swampy area, linking the airfield on Los Negros with Manus Island.

With attention focused on the opening of new operations at Hauwei Island, the 12th and the 5th Regiments began working their way south of Papitalai Mission through the rough hills and dense jungles in hand to hand combat. Tanks sometimes would give welcome support, but mostly the Troopers had to do the dangerous job with small arms and grenades.

Two final attacks wiped out the remaining resistance on Los Negros Island. On 22 March, two squadrons from the 5th and 12th Regiments overran enemy positions west of Papitalai Mission. Once again it was tough fighting with the terrain, overgrown with thick canopies of vines, favoring the Japanese. On 24 March, the 5th and 12th Regiments overcame fanatical resistance and pushed through to the north end of the island. On 28 March, the battles for Los Negros and Manus were over, except for mop up operations.

The Admiralty Islands campaign officially ended on 18 May 1944. Japanese casualties stood at 3,317 killed. The losses of the 1st Cavalry Division were 290 dead, 977 wounded and four missing in action. Training, discipline, determination and ingenuity had won over suicidal attacks. The 5th Cavalry Troopers were now seasoned Veterans.

On Columbus Day, 12 October 1944, the 1st Cavalry Division sailed away from its hard earned base in the Admiralties for the Leyte invasion, Operation King II. On October 20, the invasion force must have appeared awesome to the waiting Japanese as it swept toward the eastern shores of Leyte. Precisely at 1000 hours, the first wave of the 1st Cavalry Division hit the beach. The landing, at “White Beach” was between the mouth of the Palo River, to the south and Tacloban, the capital city of Leyte. Troopers of the 5th, 7th and 12th Cavalry Regiments quickly fanned out across the sands and moved into the shattered jungle against occasional sniper fire.

The fighting near the beaches was still was underway when General MacArthur and Philippines President Sergio Osmena waded ashore in ankle deep water. MacArthur soon broadcast his famous message to the Philippinos: “People of the Philippines: I have returned. By the grace if Almighty God, our forces stand again on the Philippine soil – soil concentrated in the blood of our two peoples… Rally to me! Rise and strike!”. To the Philippine guerilla forces and the 17 million inhabitants, it was the news they had long awaited.

The missions of the 1st Cavalry Division in late October and early November included moving across Leyte’s northern coast, through the rugged mountainous terrain and deeper into Leyte Valley. The 1st Brigade had severe fighting in most difficult terrain when the 5th and 12th Cavalry secured the central mountain range of Leyte. By 15 November, elements of the 5th and 7th Regiments pushed west and southwest within a thousand yards of the Ormoc Pinamapoan Highway. By 11 January 1945, the Japanese losses amounted to nearly 56,200 killed in action and only a handful – 389 had surrendered. Leyte had indeed been the largest campaign in the Pacific War, but the record to that was about to be shattered during the invasion of Luzon.

With the last of the strongholds eliminated, the division moved on to Luzon, the main island of the Philippines. On 26 January, conveys were formed and departed for the Lingayan Gulf, Luzon Island, the Philippines. Landing without incident on 27 January, the regiment assembled in an area near Guimba and prepared for operations in the south and southwest areas. On 31 January 1945, General Douglas MacArthur issued the order “Go to Manila! Go around the Japs, bounce off the Japs, save your men, but get to Manila! Free the internees at Santo Tomas! Take the Malacanan Palace (the presidential palace) and the legislative building!” The next day, elements of the 5th Regiment joined the “flying column”, as the mobile units came to be known, jumped off to slice through 100 miles of Japanese territory. The rescue column, led by Brigadier General William C. Chase was a high risk gamble from the beginning. The column was able to get around, over and past each obstacle in its path. At 1835, 3 February the rescue column crossed the city limits of Manila. By 2100 the internment camp at Santo Tomas was liberated and the prisoners were freed. On 7 February, the 37th Infantry Division relieved the 5th Regiment, who immediately joined in the fight to free southern sections on Manila. The First Team was; “First in Manila”.

On 12 April, the 5th Cavalry Regiment began a drive southeastward down the Bicol Peninsula to clear it of Japanese and link up with the 158th Regimental Combat team. The two forces finally converged at Naga on 29 April, after “B” Troop, 5th Cavalry and a group of engineers made an amphibious assault across the Ragay Gulf at Pasacao. On 30 June 1945, the Luzon Campaign was declared completed.

On 13 August, the 1st Cavalry Division was alerted that they were selected to accompany General Douglas MacArthur to Tokyo and would be part of the 8th Army in the occupation of Japan. On 2 September, the long convey of ships steered into Yokohama Harbor and past the battleship Missouri where General MacArthur would later receive the Japanese surrender party. At noon on 5 September 1945, a reconnaissance party headed by Colonel Charles A. Sheldon, the Chief of Staff of the 1st Cavalry Division, entered Tokyo. This embarkment was the first official movement of American personnel into the capital of the mighty Japanese Empire.

At 0800 hours on 8 September, a history making convoy left Hara-Machida with Tokyo as their destination. Headed by Major General William C. Chase, commanding general of the 1st Cavalry Division, the party included a Veteran from each troop of the division. Passing through Hachioji, Fuchu and Chofu, the Cavalry halted briefly at the Tokyo City Limits. General Chase stepped across the line thereby putting the American Occupational Army officially in Tokyo and adding another “First” to its name; “First in Tokyo”.

The first mission of the division was to assume control of the city. On 16 September, the 1st Division was given responsibility for occupying the entire city of Tokyo and the adjacent parts of Tokyo and Saitama Prefectures. The command posts of the 1st Brigade, 5th Cavalry and 12th Cavalry were situated at Camp McGill at Otawa, approximately 20 miles south of Yokohama. The 2nd Cavalry Brigade had its command post at the Imperial Guard Headquarters Buildings in Tokyo, while the 7th Cavalry was situated at the Merchant Marine School. The 8th Cavalry occupied the 3rd Imperial Guard Regiment Barracks in Tokyo, which provided greater proximity to security missions at the American and Russian Embassies and the Imperial Palace grounds. Division Headquarters and other units were stationed at Camp Drake near Tokyo.

Troops of the 5th Cavalry Regiment were assigned guard and security missions in the Tokyo area where General MacArthur had taken up residence. Over the next five years, until the outbreak of the Korean War, the regiment was able to perform many valuable duties and services that helped Japan reconstruct and create a strong, viable economy. On 25 March 1949, the reorganization which began in 1945, was completed by redesignating troops as companies.

It happened before dawn on 25 June 1950. Less than 5 years after the terrible devastations of World War II, a new war broke out from a distant land whose name means “Morning Calm”. The decision of the United States to send immediate aid to South Korea came two days after the fast moving North Korean broke through the ROK defenses and sent tanks into the capital city of Seoul. In addition to the Air Force, Navy and Marines, a 1,000 man battalion from the 24th Infantry Division, including many specialists and noncommissioned officers transferred from the 1st Cavalry Division, arrived 30 June with a promise that more help was on the way.

On 18 July, the 1st Cavalry Division was ordered to Korea. Initially scheduled to make an amphibious landing at Inchon, it was redirected to the southeastern coast of Korea at Pohang-dong a port 80 miles north of Pusan. The North Koreans were 25 miles away when elements of the 1st Cavalry Division swept ashore to successfully carry out the first amphibious landing of the Korean War. The 5th Cavalry Regiment Combat Team marched quickly toward Taejon. By 22 July, all regiments were deployed in battle positions; in itself a remarkable logistical achievement in the face of Typhoon Helene that pounded the Korean coastline.

The baptism of fire came on 23 July. The 8th Cavalry was hit by a heavy artillery and mortar barrage and North Koreans swarmed toward their positions. As the space between the battalions became increasingly threatened, the 1st Battalion, 5th Cavalry moved into the gap to absorb some of the pressure. Elements were also sent to help the 8th Cavalry. The next day, the Troopers suffered their first severe combat losses. Company “F”, 5th Cavalry moved to assist the 1st Battalion of the 5th on its right flank. Company “F”, and Company “B”, 5th Cavalry were hit by overwhelming numbers of North Korean Infantry. Only 26 men from the relief units managed to escape and return to friendly territory.

During the next few days a defensive line was formed at Hwanggan with the 7th Cavalry moving east and the 5th Cavalry replacing the 25th Infantry Regiment. On 1 August, the First Team was ordered to set up a defensive position near Kumchon on the rail route from Taegu to Pusan. For more than 50 days between late July and mid September, First Team Troopers and UN Soldiers performed the bloody task of holding on the vital Pusan Perimeter.

On 9 August, the enemy hurled five full divisions and parts of a sixth at the Naktong defenders near Taegu. The 1st Battalion, 5th Cavalry bore the brunt of this attack. The North Koreans gained some high ground – but not for long. The 1st Battalion, 7th Cavalry moved against them, hitting their flanks with coordinated artillery and air strikes. In seizing hill 268, known as “Triangulation Hill”, the Troopers accounted for 400 enemy dead. The First Team pulled back from some of its positions and tightened its defenses. The 5th Cavalry withstood two more punishing attacks. The North Korean drive ground to a halt on 8 September, seven miles short of Taegu. The momentum began to turn.

With added reinforcements, Pusan became a staging ground and depot for United Nations supplies and Soldiers from all around the world. Solders of the United Nations forces became First Team Troopers, the gallant Greek Battalion (GEF) was attached to the 7th Cavalry Regiment and fought alongside of them. The defenders now outnumbered the attackers and they had the equipment and firepower to go on the offensive.

The turning point in this bloody battle came on 15 September 1950, when MacArthur unleashed his plan, Operation CHROMITE, an amphibious landing at Inchon, far behind the North Korean lines. In spite of the many negative operational reasons given by critics of the plan, the Inchon landing was an immediate success allowing the 1st Cavalry Division to break out of the Pusan Perimeter and start fighting north.

On 26 September, the 5th Cavalry crossed the Naktong, advancing to Sanju and north to Hamchung and south to Osan-dong. Then the 5th had to seize Chongo. Chochiwon and Chouni astride the main highway were the next objectives. On 2 October, the 5th Cavalry were ordered to push north and establish a bridgehead across the Imjin River. The 5th Cavalry probed ahead crossing the 38th parallel on 9 October 1950. During the night of 11 October, Lt. Samuel S. Coursen of “C” Company, 5th Cavalry lead his men into enemy territory to reduce a roadblock that was holding up the advance. Led by the 5th Regiment, the 1st Cavalry Division entered Pyongyang, the capital of North Korea on 19 October. This event marked the third “First” for the Division; “First in Pyongyang”.

On 28 October 1950, orders came from I Corps to saddle up the rest of the division and move north. The Korean War seemed to be nearing a conclusion. The North Korean forces were being squeezed into a shrinking perimeter along the Yalu and the borders of Red China and Manchuria. By now, more than 135,000 Red troops had been captured and the North Korean Army nearly destroyed.

On 25 October 1950, the Korean War took a grim new turn. The sudden intervention of Communist Chinese forces dashed hopes of a quick end to the war. The Chinese were attacking in force. They had tanks; waves of Soldiers and fearsome weapons of the Soviet’s; rockets. On 24 November, General MacArthur launched a counteroffensive of 100,000 UN troops. The 1st Cavalry and the ROK 6th Divisions moved up from their reserve positions and slammed into the attack. The Chinese penetrated the front companies of 1st and 2nd Battalions, 7th Cavalry and tried to exploit the gap. At 0200 they were hit by elements of the 3rd Battalion reinforced by tanks. Red troops were stopped and retreated back into an area previously registered for artillery fire. Enemy losses were high and the shoulder was held.

The New Year began unexpectedly quiet. The First Team defenders readied their weapons, shored up their defenses and waited in the bitter cold. This time there was no surprise when the Chinese artillery began pounding the UN lines in the first few minutes of 1951. The units forward of the 38th Parallel were hit by the Chinese crossing the frozen Imjin River. Ignoring heavy losses, the Chinese crawled through mine fields and barbed wire. The United Nations Forces abandoned Seoul and fell back to the Han River. The Chinese drive lost its momentum when it crossed the Han and a lull fell over the front.

On 25 January 1951, the First Team, joined by the revitalized 3rd Battalion, 8th Cavalry rebounding from its tragedy at Unsan, moved back into action. The movement began as a reconnaissance in force to locate and assess the size of the Red Army, believed to be at least 174,000. The Eight Army moved slowly and methodically, ridge by ridge, phase line by phase line, wiping out each pocket of resistance before moving farther North. The advance covered 2 miles a day, despite heavy blinding snowstorms and subzero temperatures.

During this bitter fighting, another First Trooper made the highest sacrifice and won the Medal of Honor. On 29 – 30 January, the 5th Cavalry had a hard fight on its hands on Hill 312. On 30 January, 1st Lt. Robert M. McGovern led “A” Company up the reverse slope and got near the enemy on the crest before he was wounded. Realizing that his men were in danger, Lt. McGovern threw back several enemy grenades and charged a machine gun that was raking his platoon. Although wounded Lt. McGovern killed seven solders before he was fatally wounded.

On 14 February, heavy fighting erupted around an objective known as Hill 578, which was finally was taken by the 7th Cavalry after overcoming stiff Chinese resistance. During this action General MacArthur paid a welcome visit to the 1st Team. Not far away, at a town Chipyong-ni, the 23rd Regimental Combat Team and a French Army Battalion were surrounded by five Chinese divisions. In desperate fighting, the two units killed thousands of Chinese but were unable to break out.

The 5th Cavalry Regiment formed a rescue force, called Task Force Crombez, to counterattack along a road running from Yoju to Chipyong-ni via Koksu-ri, a distance of 15 miles. The Troopers had painted tiger stripes on their armored tanks to give them a psychological advantage. The sight of the tiger-striped M4A3 and M46 tanks sent many of the Chinese running from their entrenched positions. As the fleeing Chinese raced through open ground, they were cut down by heavy fire from the tanks and escorting Troopers of Company “L”, who had taken heavy casualties in their mission of tank protection enroute to Chipyong-ni. On 15 February, Task Force Crombez broke through the perimeter of Chipyong-ni ending the standoff. The victory at Chipyong-ni marked the first time in the Korean War that the Red Chinese had been dealt a major defeat.

The 1st Cavalry slowly advanced though snow and later, when it became warm, through torrential rains. The Red Army was slowly; but firmly, being pushed back. On 14 March, the 3rd Battalion, 8th Cavalry had crossed the Hangchon River and on the 15th, Seoul was recaptured by elements of the 8th Army. New objectives were established to keep the Chinese from rebuilding and resupplying their forces and to advance to the “Kansas Line”, which roughly followed the 38th Parallel and the winding Imjin River.

On 22 April, 21 Chinese and 9 North Korean divisions slammed into Line Kansas. Their main objective was to recapture Seoul. The First Cavalry joined in the defense line and the bitter battle to keep the Reds out of the South Korean Capital. Stopped at Seoul, on 15 May, the Chinese attempted a go around maneuver in the dark. The 8th Army pushed them back to the Kansas Line and later the First Team moved deeper into North Korea, reaching the base of the “Iron Triangle”, an enemy supply area encompassing three small towns.

From 9 June to 27 November, the 1st Cavalry took on various rolls in the summer-fall campaign of the United Nations. On 18 July, a year after it had entered the war, the 1st Cavalry Division was assigned to a reserve status. This type of duty did not last for long. On the nights of 21 and 23 September, the 2nd and 3rd Battalions, 7th Cavalry repulsed waves of Red Chinese with hand to hand fighting. But harder work followed when Operation “Commando”, a mission to push the Chinese out of their winter defense positions south of the Yokkok River, was launched.

On 3 October, the 1st Team moved out from Line Wyoming and immediately into Chinese fire. For the next two days; hills were taken, lost and retaken. On the third day, the Chinese lines began to break in front of the 7th Cavalry. On 5 October, the 8th Cavalry recaptured Hill 418, a flanking hill on which the northern end of Line Jamestown was anchored. On 10 – 11 October, the Chinese counterattacked; twice, unsuccessfully against the 7th Cavalry. Two days later, the 8th Cavalry took the central pivot of the line, Hill 272. The southern end of Line Jamestown, along with a hill called “Old Baldy”, eventually fell to the determined Troopers. The Troopers did not know it, but Line Jamestown would be their last major combat of the Korean War. By December 1951, the division, after 549 days of continuous fighting, began rotation back to Hokkaido, Japan.

On 27 November, the advance party from the division, left Korea. On 07 December 1951, the 5th Cavalry sailed for Hokkaido, Japan to become part of the US XVI Corps. By late January 1952, all units had arrived on Hokkaido, under the command of Major General Thomas L. Harrold. The First Team had performed tough duties with honor, pride and valor with distinction.

Arriving in the port of Muroran, each unit was loaded on trains and moved to the new garrison areas. Three camps were established outside Sappro, the Islands capital city. Division Headquarters and the 7th Cavalry Regiment were stationed at Camp Crawford. The 5th Cavalry was stationed at Camp Chitose, Area I. The 8th Cavalry, the last unit to leave Korea, was stationed at Camp Chitose, Area II. The division controlled a huge training area of 155,000 acres. The mission of the division was to defend the Island of Hokkaido and to maintain maximum combat readiness.

On 10 February 1953, the 5th Cavalry Regiment, 61st Field Artillery Battalion and Battery “A”, 29th AAA AW Battalion, departed from Otaru, Japan for Pusan and Koje-do, Korea to relieve the 7th Cavalry who had previously rotated back to Korea. On 27 April, all elements of the 5th Cavalry, less the 3rd Battalion and Heavy Mortar Company, returned to Hokkaidio. The units remaining in Korea continued security missions under control of KCOMZ.

The Korean War wound down to a negotiated halt when the long awaited armistice was signed at 10:00 on 27 July 1953. A DeMilitarized Zone (DMZ), a corridor – 4 kilometers wide and 249 kilometers long, was established dividing North and South Korea. The nominal line of the buffer zone is along the 38th parallel; however, the final negotiations of the adjacent geographical areas, gave the North Korean Government some 850 square miles south of the 38th parallel and the South Korean Government some 2,350 square miles north of it.

On 9 September, the 3rd Battalion and Heavy Mortar Company of the 5th Cavalry returned to Hokkaido after seven months of duty in Korea.

In September 1954, the Japanese assumed responsibility for defending Hokkaido and the First Team returned to the main Island of Honshu. 1st Cavalry Division Headquarters and the 5th Cavalry Regiment were located at Camp Schimmelpfennig. The 7th Cavalry Regiment and the 29th AAA AW Battalion occupied Camp Haugen, near Hachinohe. The 8th Cavalry Regiment was stationed at Camp Hachinohe. For the next three years the division guarded the northern sections of Honshu until a treaty was signed by the governments of Japan and the United States in 1957. This accord signaled the removal of all US ground forces from Japan’s main islands.

On 20 August 1957, the 1st Cavalry Division, guarding the northern sections of Honshu, Japan was reduced to zero strength and transferred to Korea (minus equipment). On 23 September 1957, General Order 89 announced the redesignation of the 24th Infantry Division as the 1st Cavalry Division and ordered a reorganization of the Division under the “pentomic” concept. As part of the “pentomic” reorganization, the 1st Battle Group, 5th Cavalry was activated, organized and assigned to the 1st Cavalry Division. In ceremonies held on 15 October, the colors of the 24th Division were retired and the colors of the 1st Cavalry Division were passed to the Commanding General of the old 24th Division, Major General Ralph W. Zwicker. “The First Team” had returned to Korea, standing ready to defend the country against Communist aggression.

The redesignated and reorganized 1st Cavalry was assigned the mission of patrolling the “Freedom’s Frontier” (DMZ). In addition to their assigned duties of patrol along the southern border of the DMZ, training remained a number one priority for the Troopers and unit commanders. In January 1958, the largest training exercise in Korea since the end of hostilities, Operation Snowflake, was conducted. This exercise was followed by Operation Saber in May and Operation Horsefly in August. In June 1965, the 5th Cavalry Regiment began rotation back to the United States along with other units of the 1st Cavalry Division.

NOTE – Although fighting was stopped, in July 1953, by the armed truce, North and South Korea have remained officially in a state of war, signified by the fact that over 1,000 UN personnel have been killed in duty at the DMZ. As of today, because of communist obstructionist tactics, years have gone by and no peace treaty has ever been agreed to and signed. An ever present “alert” status is in effect, as evidenced by the presence of a North Korean military force of 1.1 million troops stationed within miles of the Demilitarized Zone facing the South Korean force of 660,000 troops supported by 37,000 American Soldiers stationed in the area.

The roots of the Vietnam War started in 1946 with the beginning of the First Indochina War. Vietnam was under French control at that time (as was Laos and Cambodia), and the Vietnamese, under the leadership of Ho Chi Minh, wanted independence. So the Vietnamese and French fought each other in Vietnam. Eventually, in 1954, the Vietnamese defeated the French and both countries signed the Geneva Peace Accords, which, among other things, established a temporary division in Vietnam at the 17th parallel. The division of the country eventually led to the Vietnamese War.

The Geneva Accords stated that the division was to be temporary, and that national elections in 1956 would reunite the country. But the United States did not want to see Vietnam turn into a communist state, so the US supported the creation of the Southeast Asia Treaty Organization, which provided defense for South Vietnam.

North Vietnam, then called the Democratic Republic of Vietnam, wanted a communist state, and South Vietnam, then called the Republic of Vietnam, wanted a non-communist state. In 1956, Ngo Dihn Diem, an anti-communist, won the presidential election in South Vietnam. But communist opposition in the south caused Diem numerous problems. And in 1959, southern communists decided to implement greater violence to try to oust Diem. This led to the formation of the National Liberation Front (NLF).

The NLF was a group of communists and non-communists who opposed Diem and sought his ouster. In 1961, President John F. Kennedy sent a group to South Vietnam to determine what actions the US needed to take to assist them. When the group returned, they proffered recommendations in what became known as the “December 1961 White Paper” that indicated a need for an increased military presence; but many of the advisors of Kennedy wanted a complete pullout from the country.

In the end, Kennedy compromised and decided to increase the number of military advisors, but with the objective of not to engage in a massive military buildup. But in 1963, the government of Diem quickly began to unravel. The downfall began when Diem’s brother accused Buddhist monks of harboring communists — his brother then began raiding Buddhist pagodas in an attempt to find these communists

The Buddhist monks immediately began protesting in the streets, and in Saigon on 5 October, 1963, one monk died by self-immolation. This incident caused international outrage and Diem was soon overthrown and killed. On 2 August, 1964, North Vietnam attacked an American ship in the Gulf of Tonkin that resulted in congress enacted the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, which granted the president broad war powers.

Lyndon B. Johnson was the president at the time, and the Gulf of Tonkin incident and the resultant resolution marked the beginning of the major military buildup of America in the Vietnam War. In 1965, massive bombing missions by the US in North Vietnam, known as Operation ROLLING THUNDER, quickly escalated the conflict.

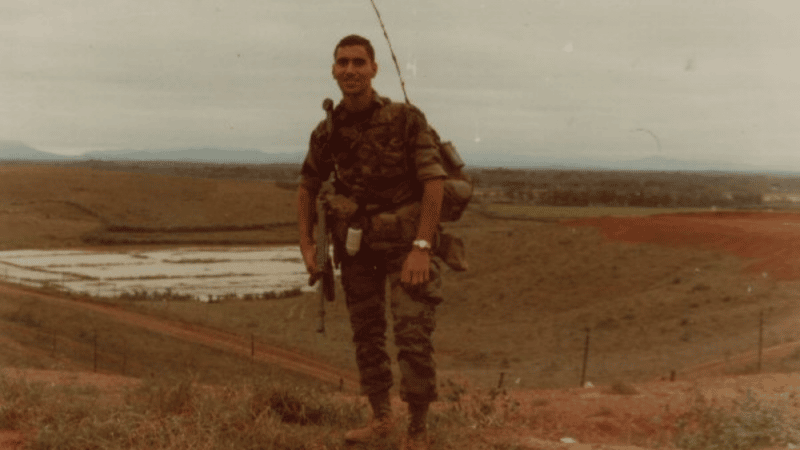

In 1965, the 1st Cavalry Division went home from the DMZ, Korea, but only long enough to be reorganized and be reequipped for a new mission. On 1 July 1965, the 1st Cavalry Division (Airmobile) was officially activated. It was made up of resources of the 11th Air Assault Division (Test) and brought to full strength by transfer of specialized elements of the 2nd Infantry Division. As a part of this reorganization, the 1st Battalion (Airborne) 38th Infantry was redesignated the 1st Battalion (Airborne), 5th Cavalry Regiment and the 2nd Battalion (Airborne), 38th Infantry was redesignated the 2nd Battalion, (Airborne), 5th Cavalry Regiment. On 3 July 1965, in Doughboy Stadium at Fort Benning, Georgia the colors of the 11th Air Assault Division (Test) were cased and retired. As the band played the rousing strains of GarryOwen, the colors of the 1st Cavalry Division were moved onto the field.

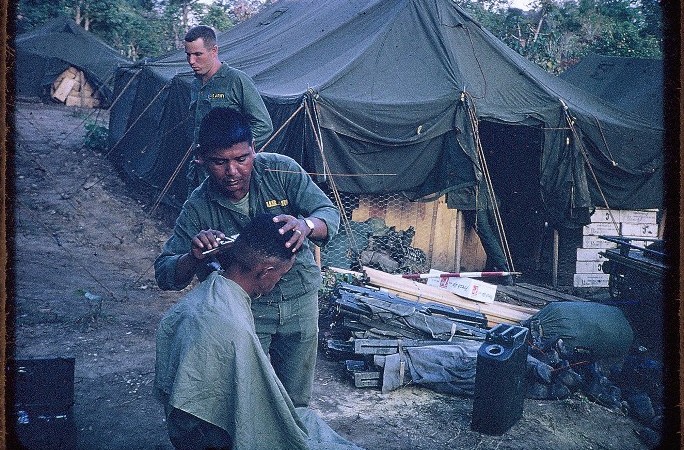

Within 90 days of becoming the Army’s first air mobile division, the First Team was back in combat as the first fully committed division of the Vietnam War. An advance party, on board C-124s and C-130s, arrived at Nha Trang between the 19th and 27th of August 1965. They joined with advance liaison forces and established a temporary base camp near An Khe, 36 miles inland from the coastal city of Qui Nhon. The remainder of the 1st Cavalry Division arrived by ship, landing at the harbor of Qui Nhon on the 12th and 13th of September, the 44th anniversary of the 1st Cavalry Division. In the Oriental calendar year of the “Horse”, mounted Soldiers had returned to war wearing the famous and feared patch of the First Cavalry Division. The First Team had entered its third war – and the longest tour of duty in combat history.

The newly arrived Skytroopers wasted little time in getting into action. From 18 – 20 September, to Troopers of the 2nd Battalion, 5th Cavalry and the 2nd Battalion, 12th Cavalry supported the 1st Brigade of the 101st Airborne Division in Operation GIBRALTAR. The operation took place 17 miles northeast of An Khe in the Vinh Thanh Valley; known as “Happy Valley” by the troops. “B” Battery of the 1st Battalion, 77th Artillery provided supporting fire.

On 23 October 1965, the first real combat test came at the historic order of General Westmoreland to send the First Team into an air assault mission to pursue and fight the enemy across 2,500 square miles of jungle. Troopers of the 1st Brigade and 1st Squadron, 9th Cavalry swooped down on the NVA 33rd regiment before it could get away from Plei Me. The enemy regiment was scattered in the confusion and was quickly smashed. The Troopers inflicted many hundreds of casualties. Hundreds of NVA troops died in the blistering, precision bombing of B-52’s.

More savage fighting erupted about a week before the campaign ended. The second Battalion, 7th Cavalry was ordered to move toward a location named “Albany”. Encountering a NVA battalion from the 66th Regiment in the dense jungle they slugged it out in grim determination. The 2nd Brigade, 1st Cavalry surged into the battle and the Vietnamese decided to cut their losses and run. When the Pleiku Campaign ended on 25 November, Troopers of the First Team had killed 3,561 North Vietnamese Soldiers and captured 157 more. The Troopers destroyed two of three regiments of a North Vietnamese Division, earning the first Presidential Unit Citation given to a division in Vietnam. The enemy had been given their first major defeat and their carefully laid plans for conquest had been torn apart.

25 January 1966, was the beginning of “Masher/White Wing” which were code names for the missions in Binh Dinh Province. On 19 – 21 February, one of the main actions occurred in an area known as the “Iron Triangle”, an elaborate, well fortified defensive position 12 miles south of Bong Son. During the interrogation of a prisoner, he revealed the location of the NVA 22nd Regimental headquarters. Elements of the 2nd Brigade advanced into the area and were met by fierce resistance. Units from the NVA 22nd Regiment attempted to reinforce their headquarters, but they were cut down in the crossfire of two companies of the 1st Battalion, 12th Cavalry. For the next three days the area was saturated with artillery fire and B-52 strikes. The mission ended 6 March 1966. With the enemy losing its grip on the Binh Dinh Province, however its name would be heard again and again during the next six years.

On 16 May, the next major mission, Operation CRAZY HORSE, commenced during the hot summer, with the temperature soaring to 110 degrees. The search and destroy assignment extended into the heavy jungle covered hills between Suoi Ca and the Vinh Thanh Valleys. The 1st Brigade went into action against the 2nd Viet Cong Regiment. Intelligence indicated that the Viet Cong were massing in a natural corridor known as the “Orgeon Trail”, planning to attack the Special Forces Camp on 19 May; the birthday of Ho Chi Minh. Initial contact was made by “B” Company, 2nd Battalion, 8th Cavalry at LZ Hereford. “A” Company, 1st Battalion, 12th Cavalry were airlifted to a nearby point to join the battle. The two companies held off superior enemy forces throughout the night. The next morning elements of the 12th Calvary and the entire 1st Brigade became involved in Crazy Horse. The fighting now consisted of short but bitter engagements in tall elephant grass and heavily canopied jungle. The battleground covered approximately 20 kilometers with the Viet Cong holed up on three hills. Once they were surrounded, all available firepower was concentrated in their area. If not killed by the devastation, those trying to flee were cut down by cavalry crossfire. On 05 June 1966, Operation CRAZY HORSE was concluded.

The need for rice by the famished Viet Cong was the catalyst for Operation PAUL REVERE II which commenced on 2 August 1966. Hill 534, on the southern portion of Chu Pong Massif near the Cambodian Border, was the location of the final battle of Operation PAUL REVERE II. It began on 14 August, after “A” Company, 1st Battalion, 5th Cavalry suddenly ran into a North Vietnamese battalion and “B” Company, 2nd Battalion began slugging it out with enemy troops in bunkers. A total of two battalions of Skytroopers were committed to the fight. When it ended the next morning, 138 NVA bodies were counted.

Operation THAYER I was one of the largest air assaults launched by the 1st Cavalry Division. Its mission was to rid Binh Dinh Province of NVA and VC Soldiers and the VC’s political infrastructure. On 16 September, Troopers of the 1st Brigade discovered an enemy regimental hospital, a factory for making grenades, antipersonnel mines and a variety of weapons. On 19 September, elements of the 2nd Battalion, 8th Cavalry traded fire with two NVA combat support companies.

In the opening phases of Operation THAYER, enemy elements of the 7th and 8th battalions, 18th North Vietnamese Army Regiment had been reported in the village of Hoa Hoi. The 1st battalion, 12th Cavalry Regiment, in the face of strong heavy resistance, deployed to encircle the village. On 2 October, “B” Company was the first to be air assaulted into the landing area 300 meters east of the village. Immediately, the units came under intense small arms and mortar fire. “A” Company landed to the southwest and began a movement northeast to the village. In the meantime, “C” Company landed north of the village and began moving south. By this time “A” and “B” Companies had linked up and established positions which prevented the enemy from slipping out of the village during the night.

During the course of the evening, “A” and “C” Companies, 1st Battalion, 5th Cavalry Regiment were airlifted into an area east of the village to assist in the containment of the enemy. Additional support of artillery forward observers from “A” Battery, 2nd Battalion, 19th Artillery helped as the enemy locations were identified and called in during the night.

In the morning of 3 October, “C” Company, 1st Battalion, 12th Cavalry and “C” Company, 1st Battalion, 5th Cavalry attacked south to drive the remaining enemy forces into “A” and “B” Companies, 12th Cavalry who were braced in blocking positions to take the attack. This last action broke the strong resistance of the enemy and mission was completed.

On 31 October, Operation PAUL REVERE IV was launched by the 2nd Brigade. Its units included; 1st Battalion, 5th Cavalry; 2nd Battalion, 12 Cavalry; “B” Company. 1st Squadron, 9th Cavalry and the 1st Battalion, 77th Artillery. The operation called for an extensive search and destroy mission in the areas of Chu Pong and the Ia Drang Valley, as well as along the Cambodian Border. With only one exception only light contact with the enemy was achieved. In mid-morning of 21 November, “C” Company, 1st Battalion, 5th Cavalry was searching south of Duc Co along the border. Suddenly the 2nd Platoon began trading fire with a NVA force of significant size. The 3rd Platoon went to the aid of the 2nd Platoon. The two units, outnumbered by large numbers of North Vietnamese, fought desperately.

The 3rd Platoon was overrun in fairly short order with only one man surviving – it happened before they were able to call in any effective artillery or air support. The 2nd Platoon took over 50% casualties but was not overrun – they had 13 or 14 KIA and about as many wounded. As was typical in the early days of the Vietnam War, many of their M-16s had malfunctioned early in the fight. With the dense foliage, neither artillery nor helicopter gunships were very effective in providing support. The remnants of 2nd Platoon was saved by the arrival of a flight of Skyraiders equipped with napalm. They were accurate enough to put the canisters right on the attacking NVA. The 1st Platoon arrived a few minutes after the airstrike and linked up with 2nd Platoon. Except for a few stray rounds from the departing NVA, the battle was over. The foliage was too thick to cut an LZ and the wounded were lifted out one by one by Hueys equipped with winches. The KIA’s were placed in a cargo net and was lifted out by a Chinook. “A” Company located the ambush site of 3rd Platoon and medevaced the one survivor. The 101 “C” Regiment of the 10th NVA Division paid a very high price for its victory. It lost nearly 150 of their men. On 27 December, Operation PAUL REVERE IV was closed out and 2nd Brigade Troopers added their strength to Operation THAYER II.

As 1967 dawned, the 1st Brigade began making new contacts with the enemy units in central and southern Kim Son Valley, while the 2nd Brigade began a sweep to the north, flushing the enemy from their position in the north end of the valley as well as the Crescent Area, the Nui Mieu and Cay Giep Mountains. On 27 January heavy fighting with the 2nd Battalion, 12th Cavalry launching an air assault in the midst of an NVA battalion northeast of Bon Son. In THAYER II, the enemy once again had suffered punishing losses of 1,757 men.

On 13 February 1967, Operation PERSHING began in a territory which was familiar to many skytroopers, the Bong Son Plain in northern Binh Dinh Province. For the first time, the First Cavalry Division committed all three of its brigades to the same battle area.

The Division began 1968, by terminating Operation PERSHING, the longest of the actions by the 1st Cavalry Division in Vietnam. When the operation ended on 21 January, the enemy had lost 5,401 Soldiers and 2,400 enemy Soldiers had been captured. In addition, some 1,500 individual and 137 crew weapons had been captured or destroyed.

Moving to I Corps, Vietnam’s northern most tactical zone, the division set up Camp Evans for their base camp. On 31 January 1968, amid the celebration of the Vietnamese New Year, the enemy launched the Tet Offensive, a major effort to overrun South Vietnam. Some 7,000 enemy, well equipped, crack NVA regulars blasted their way into the imperial city of Hue, overpowering all but a few pockets of resistance held by ARVN troops and the US Marines. Within 24 hours, the invaders were joined by 7,000 NVA reinforcements. Almost simultaneously to the North of Hue, five battalions of North Vietnamese and Viet Cong attacked Quang Tri City, the capital of Vietnam’s Northern Province.

The 1st Brigade was not far from Quang Tri when the attacks began and was soon called to help the ARVN defenders. Four companies of skytroopers from the 1st Battalions of the 5th and 12 Cavalry Regiments quickly arrived at hot LZs around the Valley of Thon An Thai, just east of Quang Tri. The Troopers knocked out the heavy weapons support of the NVA and squeezed the enemy from the rear. The enemy soon broke off the Quang Tri attack and split into small groups in an attempt to escape. For the next ten days, they would find themselves hounded by the 1st Brigade.

After shattering the enemy’s dreams of a Tet victory, the “Sky-Troopers” of the 1st Cavalry Division initiated Operation PEGASUS to relieve the 3,500 US Marines and 2,100 ARVN Soldiers besieged by nearly 20,000 enemy Soldiers. On 1 April 1968, the 3rd Brigade, making a massive air assault within 5 miles of Khe Sanh, were soon followed by the 1st and 2nd Brigades and three ARVN Battalions. “A” Company, 2nd Battalion, 7th Cavalry led the way, followed by “C” Company, 2nd Battalion, 7th Cavalry. After four days of tough fighting, they marched into Khe Sanh to take over the defense of the battered base. Pursing the retreating North Vietnamese, the 1st Battalion, 12th Cavalry recaptured the Special Forces camp at Lang Vei uncovering large stockpiles of supplies and ammunition. The final statistics of Operation PEGASUS were 1,259 enemy killed and more than 750 weapons captured.

On 19 April 1968, Operation DELAWARE was launched into the cloud-shrouded A Shau Valley, near the Laotian border and 45 kilometers west of Hue. None of the Free World Forces had been in the valley since 1966, which was now being used as a way station on the supply route known as the Ho Chi Minh Trail. The first engagement was made by the 1st and 3rd Brigades. Under fire from mobile, 37 mm cannon and 0.50 caliber machine guns, they secured several landing zones. For the next month the brigades scoured the valley floor, clashing with enemy units and uncovering huge enemy caches of food, arms, ammunition, rockets, and Russian made tanks and bulldozers. By the time that Operation DELAWARE was ended on 17 May, the favorite Viet Cong sanctuary had been thoroughly disrupted.

On 27 June, as part of Operation JEB STUART III, the 3rd Squadron, 5th (Armored) Cavalry, 9th Infantry Division operating under the control of the 2nd Brigade, 1st Cavalry Division, had been assigned the mission of securing the Wunder Beach Complex and the access road to Highway 1, not far from Camp Evans. At 0900 hours “C” Troop, 3rd Squadron, 5th (Armored) Cavalry and “D” Troop, 1st Squadron, 9th Cavalry came under Rocket Propelled Grenade (RPG) fire as they were engaged in a detailed search of an area known as “The Street Without Joy”. As an indication of a battle to come, the residents of the nearby seacoast village of Binah An, Quan Tri Province, began to flee the area. In the attempt to detain and question the villagers, a NVA solder, hiding among the crowd, was captured and interrogated. He revealed that the entire 814th NVA Infantry Battalion was in the village. “A” and “B” Troops of the 3rd Squadron, 5th Cavalry along with “D” Troop, 1st Squadron, 9th Cavalry closed on the village, joining “C” Troop, 3rd Squadron. There was no good way of the enemy to escape during daylight hours due to the clear view and superior firepower of the surrounding forces.

In addition to the control fire directed at the enemy in the village, additional firepower of aerial rocket and Marine artillery, from Quang Tri, was made available along with Tactical Air Control (TAC) aircraft from Da Nang and a naval destroyer, with five inch guns, offshore. In the next seven hours, all of the firepower pounded the enemy to reduce the position of the enemy. During the afternoon, “D” Company, 1st and “C” Company, 2nd Battalions, 5th Cavalry, airlifted into an adjacent LZ and closed on the village. Due to the possibility of the enemy infiltrating the lines during the night, it was decided to overrun the position of the enemy and destroy their capability for effective operations during the night. The guided missile cruiser USS BOSTON arrived at dusk and in an all night bombardment her basic load of eight inch shells were exhausted. It was a nervous night for the enemy Soldiers within the tight cordon. Unorganized, some of the survivors attempted individual escapes and were soon rounded up with tanks having turret mounted searchlights and two swift Navy patrol boats operating close to the shoreline. At 0930 hours, the next morning, a final assault was made on the enemy. In the after battle assessment, two hundred thirty-three of the 814th NVA Infantry Battalion were KIA and forty-four were taken as Prisoners of War (POW) with the 5th Cavalry units experiencing only three causalities. (Editor’s Note: This was the first time that lineage elements of the original “A”, “B” and “C” Troops, 5th Cavalry Regiment had fought as a consolidated unit since 1943 in World War II.

In late 1968, the Division moved and set up operations in III Corps at the other end of South Vietnam. In late 1968, and the beginning of 1969, found the 1st Cavalry Division and the ARVN forces engaged in Operation TOAN THANG II. In the first three weeks of fighting, skytroopers killed nearly 200 enemy troops and uncovered one of the largest caches of munitions found in the Vietnam War. Also in January, Air Cavalry Troopers briefly became known as “Nav Cav” as they boarded river boats and helped patrol the Vam Co Dong River and Bo Bo Canal network. In February 1969, Operation CHEYENNE SABRE began in areas northeast of Bien Hoa. The year 1969 ended in a high note for the 1st Cavalry Division. The enemy’s domination of the northern areas of III Corps had been smashed – thoroughly.

On 1 May 1970, the First Team was “First into Cambodia” hitting what was previously a Communist sanctuary. President Nixon has given the go-ahead for the surprise mission. Pushing into the “Fish Hook” region of the border and occupying the towns of Mimot and Snoul, Troopers scattered the enemy forces, depriving them of much needed supplies and ammunition. On 8 May, the Troopers of the 2nd Brigade found an enemy munitions base that they dubbed “Rock Island East”. Ending on 30 June, the mission to Cambodia far exceeded all expectations and proved to be one of the most successful operations of the First Team. All aspects of ground and air combat had been utilized. The enemy had lost enough men to field three NVA divisions and enough weapons to equip two divisions. A year’s supply of rice and corn had been seized. The Troopers and the ARVN Soldiers had found uncommonly large quantities of ammunition, including 1.5 millions rounds for small arms, 200,000 antiaircraft rounds and 143,000 rockets, mortar rounds and recoilless rifle rounds. The sweeps turned up 300 trucks, a Porsche sports car and a plush Mercedes-Benz sedan.

The campaign had severe political repercussions in the United States for the Nixon Administration. Pressure was mounting to remove America’s fighting men from the Vietnam War. Although there would be further assault operations, the war was beginning to wind down for many Troopers.

The efforts of the 1st Cavalry Division were not limited to direct enemy engagements but also, using the experiences gained during the occupation of Japan and Korea, encompassed the essential rebuilding of the war torn country of South Vietnam. As a result of its’ gallant performance, the regiment was awarded two presidential Unit Citations and the Valorous Unit Citation.

Although 26 March 1971 officially marked the end of duties in Vietnam for the 1st Cavalry Division, President Nixon’s program of “Vietnamization” required the continued presence of a strong US fighting force. The 2nd Battalion of the 5th Regiment, 1st Battalion of the 7th Regiment, 2nd Battalion of the 8th Regiment and 1st Battalion of the 12th Regiment along with specialized support units as “F” Troop, 9th Cavalry and Delta Company, 229th Assault Helicopter Battalion helped establish the 3rd Brigade headquarters at Bien Hoa. Its primary mission was to interdict enemy infiltration and supply routes in War Zone D.

The 3rd Brigade was well equipped with helicopters from the 229th Assault Helicopter Battalion and later, a battery of “Blue Max”, aerial field units and two air cavalry troops. A QRF (Quick Reaction Force) – known as “Blue Platoons”, was maintained in support of any air assault action. The “Blues” traveled light, fought hard and had three primary missions; 1) to form a “field force” around any helicopter downed by enemy fire or mechanical failure; 2) to give quick backup to Ranger Patrols who made enemy contact; and 3) to search for enemy trails, caches and bunker complexes.

“Blue Max”, “F” Battery, 79th Aerial Field Artillery, was another familiar aerial artillery unit. Greatly appreciated by Troopers of the 1st Cavalry, its heavily armed Cobras flew a variety of fire missions in support of the operations of the 3rd Brigade. The pilots of “Blue Max” were among the most experienced combat fliers in the Vietnam War. Many had volunteered for the extra duty to cover the extended stay of the 1st Cavalry Division.

Most of the initial combat for the new brigade involved small skirmishes. But the actions became bigger and more significant. Two engagements in May of 1971 were typical operations. On 12 May, the third platoon, Delta Company, 2nd Battalion, 5th Cavalry tangled with enemy forces holed up in bunker complexes. With help from the Air Force and 3rd Brigade Gunships, the Troopers captured the complex. Fifteen days later, helicopters of Bravo Troop, 1st Squadron, 9th Cavalry received ground fire while conducting a reconnaissance mission over a large bunker complex. Air strikes were called in and the Troopers overran the complex.

Early in June, intelligence detected significant enemy movement toward the center of Long Khanh Province and its capital, Xuan Loc. On 14 June, Delta Company of the 2nd Battalion, 5th Cavalry ran into an ambush in heavy jungle and engaged a company-sized enemy unit. The Troopers were pinned down in a well-sprung trap. Cavalry field artillery soon pounded their North Vietnamese positions and heavy Cobra fire from Blue Max, “F” Battery of the 79th Aerial Field Artillery, swept down on the enemy positions keeping pressure on the withdrawing North Vietnamese throughout the night. The timely movements of the Brigade had thwarted the enemy build up north of Xuan Loc.

By 31 March 1972, only 96,000 US troops remained to be involved in the Vietnam combat operations. In mid June 1972, the stand-down ceremony for the 3rd Brigade was held in Bein Hoa and the colors were returned to the United States. The last Trooper left from Tan Son Nhut on 21 June, completing the recall of the Division which had started on 05 May 1971. With the 3rd Brigade completing their withdrawal, the 1st Cavalry had been the first Army division to go to Vietnam and the last to leave. “Firsts” had become the trademark of the First Team.

On 27 January 1973, a cease-fire was signed in Paris by the United States, South Vietnam, North Vietnam, and the Provisional Revolutionary Government of the National Liberation Front (NLF), the civilian arm of the South Vietnam Communists. A Four-Party Joint Military Commission was set up to implement such provisions as the withdrawal of foreign troops and the release of prisoners. An International Commission of Control and Supervision was established to oversee the cease-fire.

Fort Hood, Texas had begun its own long history beginning on 15 January 1942, when the War Department announced that a camp, to be a permanent station of the Tank Destroyer and Firing Center, would be built in the vicinity of Killeen, Texas. Orders were issued for the Real Estate Branch of the Engineer Corps to acquire 10,800 acres of land northwest of Killeen. On 17 February 1942, the Army announced that the camp would be named Camp Hood in honor of General John Bell Hood, the “Fighting General” of the famous “Texas Brigade” of the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia, who was later Commanding General of the Confederate Army of Tennessee.

Although not a native of Texas, General Hood was nevertheless considered a state hero for his connections with the “Texas Brigade and his prior service and dramatic forays in Texas while serving in the 2nd Cavalry Regiment (redesignated 10 August 1861, as the 5th Cavalry Regiment) at Ft. Mason, TX under Lieutenant Colonel Robert E. Lee. During the construction phase, the Army purchased an additional 16,000 acres of land in Bell County for training purposes and 34,943 acres in Coryell County for a cantonment to house the Tank Destroyer Basic Replacement Training Center and an area for its extensive field training.

On 26 March 1971, a Stand Down Ceremony at Bein Hoa, marked the departure of the 1st Cavalry Division from Vietnam. With the simple but brief ceremony highlighted by the 1st Cavalry Division Band and the bright colors, their tour of duty came to a close. After sixty-six months “in country” and continuously in combat, the First Team left the 3rd Brigade (Separate) to carry on.

On 5 May 1971, after 28 years, the colors of the 1st Cavalry Division, minus those of the 3rd Brigade, were moved from Vietnam to Texas, its birthplace. Using the assets and personnel of the 1st Armored Division, located at Fort Hood, Texas the 1st Cavalry Division was reorganized, reassigned to III Corps and received an experimental designation of the Triple-Capability (TRICAP) Division. Its mission, under the direction of Modern Army Selected Systems Test, Evaluation and Review (MASSTER) was to carry on a close identification with and test forward looking combined armor, air cavalry and airmobile concepts. The new 1st Cavalry Division consisted of the 1st Armored Brigade, the 2nd Air Cavalry Combat Brigade (ACCB) the 4th Airmobile Infantry Brigade, which the 1st Battalion, 5th Cavalry, formally the 2nd Battalion, 46th Infantry, was assigned. Division Artillery provided the fire support and Support Command provided normal troop support and service elements.

TRICAP, an acronym for TRIple-CAPability, was derived from combining the ground (mechanized infantry or armor) capability, airmobile infantry and air cavalry or attack helicopter forces. TRICAP I was held at Fort Hood, Texas beginning in February 1972. The purpose of TRICAP I was to investigate the effectiveness and operational employment of the TRICAP concept at battalion and company levels when conducting tactical operations in a 1979 European mid-intensity warfare environment. The exercise consisted of six phases; movement to contact, defense and delay, exploitation, elimination of penetration, rear area security and night elimination of penetration in an adjacent area.

On 26 June 1972, the 2nd Battalion, 5th Cavalry along with the 3rd Brigade (Separate) was brought back to the United States, completing the last stage of the “Vietnam recall” for the 1st Cavalry Division which had started over a year earlier on 5 May 1971. On 31 July, the 2nd Battalion was inactivated at Fort Hood, Texas. Their period of inactivation was short lived. On 20 June 1974, the 2nd Battalion, 5th Cavalry Regiment was reactivated, redesignated 2nd Battalion, (Armor), 5th Cavalry and reassigned to the 1st Cavalry Division, Fort Hood, Texas.

The main body of the 1st Cavalry Division, at Fort Hood, under the direction of MASSTER, continued to test future concepts of mobility and flexibility on the battlefield. The tests continued for three and a half years were very demanding. It was concluded that the employment of the TRICAP concept at the battalion level appeared to have application in some tactical situations, but employment at company level appeared to be feasible only for short periods of combat and for special missions. Evaluation also indicated that air cavalry would normally be controlled above the company level. The battalion task force encountered no combat support problems directly attributable to the TRICAP concept.

On 21 February 1975, the end of TRICAP evaluations, the mission of airmobile anti-armor warfare was transferred to the 6th Cavalry Brigade (Air Combat) co-located at Fort Hood, Texas and the 1st Cavalry Division was reorganized and redesignated to become the newest Armored Division in the Army, essentially the battle configuration it retains today. On 16 September 1986, the 2nd Battalion, 5th Cavalry Regiment was relieved from the 1st Cavalry Division and assigned to the 3rd Armored Division in Germany and inactivated on 16 December. On 16 January 1987, the 2nd Battalion was reactivated and reassigned to the 1st Cavalry Division, Fort Hood, Texas where it has been to the present, filling out the present organization structure.

In 1980, as part of the continuous preparation for combat of the unknown enemies of the future, the division was chosen to field test the new XM-1 tank. At the same time the division shed the battle weary M551 Sheridan armored reconnaissance airborne assault vehicles for M60 tanks.