99th Field Artillery Battalion

Organization and Preparation for Combat

The number “99” was attached to field artillery outfit in 1933, when a pack howitzer unit was constituted as the 99th Field Artillery Regiment. Although designated as a unit of the Regular Army, it remained inactive for almost seven years.

With the increasing threat of war, many units were called to active duty, one of them being the 99th Field Artillery. On June 1, 1940, the 1st Battalion of the Regiment was activated at Fort Hoyle, Edgewood Arsenal, Maryland; while on the same date the 2nd Battalion came into active status at Fort Lewis, Washington.

A few months after its activation the Regiment was split, and the 1st Battalion became the 99th Field Artillery Battalion while the personnel and equipment of the 2nd Battalion were reorganized as the 98th Field Artillery Battalion.

During 1941 and 1942 the 99th Field Artillery trained as a pack 75mm howitzer organization at Fort Bragg, North Carolina and Camp Hale, Colorado. It was assigned to the 1st Cavalry Division on March 2, 1943 and sailed from the United States bound for the South Pacific. Immediately prior to the 99th’s departure, the mules, which had characterized this unit, were replaced by jeeps.

Of special interest is the organization of the 1st Cavalry Division at this time. It was the only Square Division left on active duty, which meant that it had four regiments instead of the three that was normal at that time. Each regiment retained the flavor of its Cavalry background keeping such designations as squadrons and troops instead of battalions and companies.

The Artillery element of the Division consisted of three light howitzer battalions. The 61st Field Artillery Battalion had 105mm snub-nosed howitzers pulled by one and one half ton trucks. The 82nd Field Artillery Battalion and the 99th Field Artillery Battalion had 75mm pack howitzers towed by jeeps.

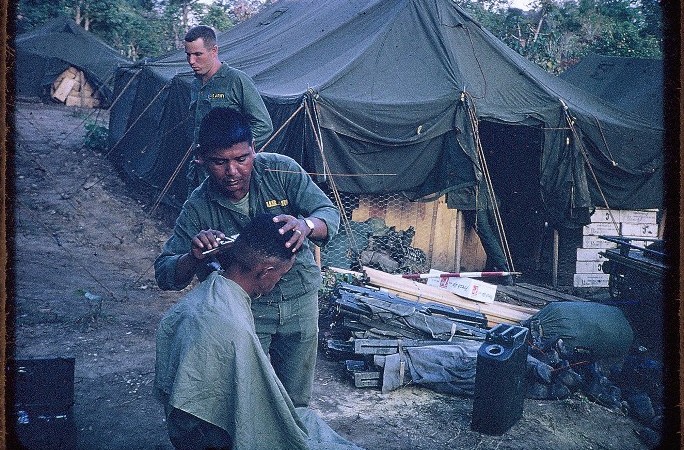

The last elements of the Division arrived at Strathpine, Australia (approximately fifteen miles north of Brisbane) on July 26, 1943. There, for the next six months, the entire Division was busily engaged in amphibious training, jungle training and the building of their camp into a showplace known as “the most beautiful military establishment in Australia”. Coupled with work was entertainment. The Cav entertained, not only themselves, but the Australians, with such spectacles as rodeos and field meets.

Tactical lessons learned from action in the Pacific precipitated the need for an additional Direct Support Field Artillery Battalion. As a result of this, the 271st Field Artillery Battalion was organized on October 11, 1943 from excess personnel from other battalions. The tempo of modern warfare began to catch up with the Division Artillery, and in October of 1943, the 61st and 271st received standard 105mm howitzers and 2 1/2 ton trucks. Four months later, they were exchanged for tractors, while the 99th and 82nd were supplied 3/4 ton trucks. Thus equipped and organized, the Division Artillery entered combat in the Admiralty Islands.

The Admiralty Islands Campaign

The 99th Field Artillery Battalion first saw action when, as a part of a reconnaissance force, it moved through the warm blue waters to the palm-fringed shores of Los Negros Island on February 29, 1944. With the force itself, was a portion of “B” Battery. The remainder of the Battalion was with the reconnaissance-support force. Although the landing caught the Japanese off guard and the initial resistance was small, it increased as the Americans moved toward Momote Airstrip and the razorback hills of the northern part of the island.

The action at Los Negros was described by the Associated Press as, “one of the most brilliant maneuvers of the war.” Typical of the fighting heart of these “redlegged mountaineers” of the 99th were such men as Private Andrew R. Barnabei, a member of Battery “B”, who heard Japanese voices in the vicinity of his foxhole. He calmly laid a grenade outside of the hole, which killed five Japanese but also disclosed his own position, thereby subjecting him to concentrated attacks by enemy patrols. Other reports include such valorous acts as Corporal Clarence W. Josephson, Battery “A”, in carrying ammo to “keep ’em shootin” amid enemy fire, and Lieutenant Colonel Kenneth L. Johnson, Commanding Officer of the 99th, for personal direction of his Battalion in the face of direct fire by the enemy.

At about the same time, heavy enemy fire threatened to explode the ammunition dump where two men of “C” Battery, Private Carle E. Derringer and Corporal Henry W. Patrick, were loading new rounds for transport to their battery’s gun position. Nevertheless, they completed their mission, thus enabling the battery to continue its fire support and contribute to the defeat of the enemy. During one of the enemy’s fierce night infiltration attacks, Lieutenant Horace E. Beaman of Battery “C” left the safety of his own shelter under heavy enemy fire to remove a fellow wounded officer of the 99th from a dangerously exposed position.

On 9 March, the 8th Cavalry Regiment and part of the 7th Cavalry landed, with the 61st Field Artillery Battalion attached, to aid in the final clean-up of the island.

Following Los Negros, the 1st Cavalry Division captured nearby Manus Island and the Admiralty Islands Campaign was terminated on May 18, 1944.

The Leyte-Samar Campaign

At approximately 2200 hours on the night of October 20, 1944, the assault waves of the 5th, 7th and 12th Cavalry Regiments with all elements of Division Artillery in support, landed on the jagged coast of Leyte. The fighting, besides being fierce and savage, was further complicated by the tortuous paths and the hand-carrying of all supplies and equipment forward to the fighting elements. Ammunition, for example, was packed on 50 pound units. In one instance, the journey on foot form the Service Battery supply points to the firing batteries required four days.

In the fight for Samar, one gun section of “C” Battery was displaced to an island where they could bring fire to bear on the objective of the 8th Cavalry Regiment. The movement was accomplished by using small native outriggers – no small feat.

The Division History has this much to say about the Artillery during this campaign: “Highlighted throughout the campaign was the invariable dependability of the Artillery. This arm inspired and fulfilled every confidence. Each of the Cavalry Regiments boasted of the proficiency of the particular Artillery Battalion assigned to its direct support. Repeatedly the Artillery opened the path for advance by cracking positions that offered the toughest opposition to the Cavalry troops. Fire brought down to within 50 yards of frontline troops was commonplace. Frequently, high-ranking Artillery officers went to the front to obtain first-hand information of the problems which daily confronted forward observers. The fine spirit of brotherly cooperation which existed between the Cavalry and the Artillery commanders assured the success which resulted from the Artillery’s incomparable support. Every available item of Artillery equipment, the most notable of which were tractors and trailers, was made available to assist in solving the ever pressing problem of supply. The 1st Cavalry Division Artillery, commanded by Brigadier General Rex Chandler, made an outstanding contribution to the success of the campaign.”

The Luzon Campaign

The 1st Cavalry Division landed in the Mabilao are of Lingayen Gulf on January 27, 1945, prepared to contribute their part to the successful conclusion of the Luzon Campaign. Three days later, after assembling some 35 miles inland, the Division received the stirring order from General MacArthur to, “Go to Manila, Go around the Nips, bounce off the Nips, but go to Manila. Free the internees of Santo Tomas. Take Malacanun Palace and the Legislative Building.” Without a chance for preliminary reconnaissance, the Division was formed into a mobile spearhead. The 99th Field Artillery Battalion was not a part of the initial spearhead, but fought in support of the 7th and 8th Cavalry Regiments. The 99th furnished the supporting fires which helped to crush the Shimbo Line in front of Antipolo. Two members of the 99th, Private James G. McLeroy and Lieutenant Rocco Stiglani of Battery “C”, earned the Silver Star by sticking to their observation posts in the face of fierce enemy attacks while supporting the 7th Cavalry Regiment in the vicinity of Maipat Hill on April 6, 1945.

Occupation of Japan

The surrender of Japan meant for the men of the 1st Cavalry Division that they were through spilling their blood on the islands of the South Pacific. On September 2, 1945, the 1st Cavalry Division made an assault landing in the harbor of Yokohama, and spread out to guard important installations in this area. Later, Division Artillery, which had been located in Yokohama, and the Infantry elements, which were located in Tokyo proper, moved to the Japanese Army Military Preparatory School at Asaka. The camp later became Camp Drake named in honor of Colonel Royce A. Drake, former commander of the 5th Cavalry Regiment . At the end of the first eighteen months of the occupation, the Division Artillery headquarters was located at Ojima, approximately 50 miles northwest of Tokyo, where it could control the four Artillery Battalions occupying the mountainous prefectures which comprised the northern portion of the Division’s zone of responsibility.

In March 1949, the 1st Cavalry Division was reorganized as a Triangular Division and became the 1st Cavalry Division (Infantry). The 12th Cavalry Regiment was deactivated and most of its members transferred to the 7th Infantry Division, while the 271st Field Artillery Battalion was redesignated as the 77th Field Artillery Battalion. This deactivation brought the First Team down to the size of a normal Infantry Division.

The Artillery continued to improve its accuracy and techniques with weekly firing exercises at Camp Weir, located about 80 miles northwest of Tokyo. It had been a long, tough road from Australia to Japan and the men of the Division settled into the more pleasant occupation duty with its nights in Tokyo and weekend tours of the country. Then it happened…

The Korean War – The Pusan Perimeter and Breakout

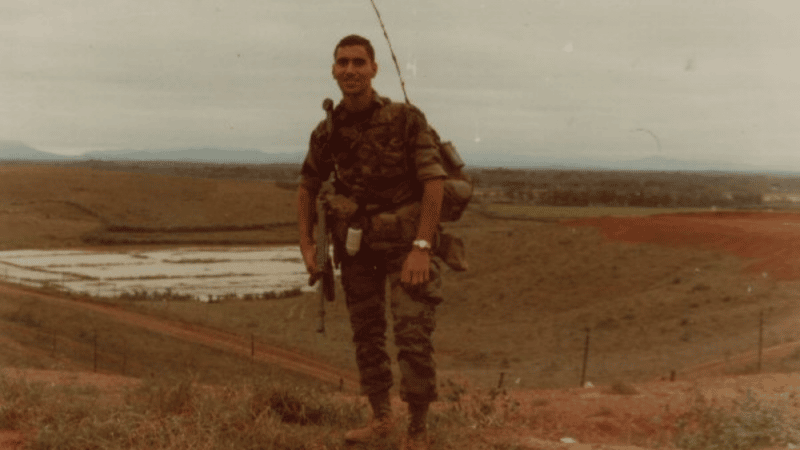

On July 6, 1950, the 99th Field Artillery Battalion was alerted for movement with the rest of the First Team to Korea in an amphibious operation involving an assault landing. Odds were long and stakes were high that summer day, 18 July, when the 99th moved ashore to enter the stab-in-the-back war in Korea. In the small harbor of Pohang-dong, just 25 miles from the raging inferno of the advancing communists, Lieutenant Colonel Phillip L. Miller’s “Redlegs”, of the 99th Field Artillery Battalion were unloaded with the first amphibious landing of the Korean War.

During that clear, hot day, the Redlegs had justifiable doubts as to how well they would do their job. As all men do, upon entering battle, they wondered and made their own estimate of the situation. Tactically the situation could have been better, and more supplies would have been helpful, but stock levels were high on only one item for combat – morale. The next 18 months would prove how well supplied the Redlegs were in this item.

Being one of the first elements ashore along with the 8th Cavalry Regiment, the 99th Field Artillery was dispersed to areas west and southwest of Pohang-dong. While readying in these areas, the men in red braid knew the months of practice were over.

After moving forward to Yong Dong, the first contact with the enemy was made on July 22, 1950. On that day, the 99th Field Artillery Battalion fired their first rounds in direct support of the 8th Cavalry Regiment. At that first bitter baptism of fire, front lines, as such, did not exist. The 99th Field Artillery repelled enemy attacks that had the cannoneers fighting with small arms along side their thundering artillery pieces. Mortar and Artillery fire fell on their positions, adding their toll to the mounting Trooper casualties.

The ferocity of the enemy, as he grew more and more anxious to press forward and seize Taegu, caused the Division to pull back some of its forces and tighten its defenses. Artillery duels with the Reds were so one sided, because of the shortage of ammunition, that the 99th was forced to displace three times during the period and “A” Battery was forced to displace once more.

The 99th Field Artillery Battalion supported various breakthroughs of the Pusan Perimeter, and on 9 October, the First Team crossed the 38th Parallel on the way to Pyongyang, the North Korean capital. Upon occupancy of the city, the 99th spent an increasing amount of time in non-combat activities.

Unsan

Due to enemy resistance north of Pyongyang, the Redlegs moved out with the 8th Cavalry to Unsan, where on the night of November 1, 1950, the Regiment, occupying the most advanced position, was hit and overrun by an overwhelming force of Chinese forces. The 99th and the 8th Cavalry attempted to withdraw, but were cut to pieces by the Red horde. Abandoning their vehicles, the Troopers plunged into the undergrowth and fought hand to hand with the Communists. Some of the men were able to escape into the darkness; the majority were killed or captured. Nearly all of the equipment was lost through damage or capture. Bearing this loss with the men, vehicles and 12 howitzers of the 99th Field Artillery Battalion.

Under the cover of the 7th Cavalry Regiment, the remainder of the 99th moved south with the rest of the Division to an assembly area where they received replacements and badly needed vehicles and howitzers. After small continuous skirmishes around Songchou, the 99th withdrew with the 1st Cavalry Division to a new area just six miles north of Seoul, where they went into Eighth Army reserve.

After being in reserve for a short period of time, the 99th returned to action supporting the 8th Cavalry in defense of the capital city of Seoul. On January 3, 1951, the order was received to evacuate the Seoul-Mehon area.

Moving North Again

The enemy showing no inclination to push south of the Han River, put doubts in the mind of General Ridgeway. To erase those uncertainties, an order to establish an armored task force to probe the enemy’s line was published. This task force was appropriately called Task Force Johnson for the commanding officer of the 3rd Battalion, 8th Cavalry Regiment.

“C” Battery was destined to give direct support in the coming one-day operation. The task force was a success and valuable lessons were learned for future planning. Task Force Johnson started a series of offensive moves north due to the lack of enemy resistance in that area.

In January and February of 1951, the rain was heavy and the Han River rose steadily in its banks. Artillery positions were quagmires and the main supply route was a river of mud. Fighting took place at various stages of the travel to the north, and the Division Artillery, hindered by mud and the enemy, forded the Han to keep within shooting distance of the enemy. The 99th stayed in position supporting various probing attacks and patrols until 3 March when the Division started to move towards the 38th Parallel again. By April, the fighting was taking place in the area south of Hwachon and north of the 38th Parallel.

Movement South and Stalemate

The 99th Field Artillery Battalion was in general support until April 28, 1951 when the Division, as a unit, was ordered to defend the Seoul sector of the front. Again the 99th supported various attacks in which the First Team made their third journey across the 38th Parallel and into North Korea. This time the lunge was north of Yonchon and along the Mjan River where the Cavalrymen played “cat and mouse” with the enemy. At this time, names such as “Bloody Ridge”, “Punchbowl” and “Heartbreak Ridge” were appearing in the news.

On the morning of the third of October, at 0600 hours Operation COMMANDO began. The 99th Field Artillery Battalion supported various stages of this operation to the north. The mission was accomplished when Phase Line Jamestown fell to the Cav four days later, but only by the sweat and blood of the Troopers of the First Team. The offensive, defensive, touch-and-go fighting continued along Phase Line Jamestown just north of Yakkok until the end of October. In early November, Hill 346, commonly known as “Old Baldy”, boned itself into the issue. From then on it was a stalemate; a jab here, a probe there, every foot of the ground costing the First Team men and equipment, but costing the enemy more that three times the price. Finally the 1st Cavalry Division was replaced by the “Thunderbirds” of the 45th Infantry Division and on December 30, 1951 the last of the 99th Field Artillery left Inchon for the move to Camp Chitose II on Hokkaido Island, Japan.

Camp Chitose II and Another Amphibious Landing

Upon arriving at Camp Chitose II, the 99th Field Artillery Battalion began a life of garrison duty and training, which consisted of Section, Winter, and Amphibious training as well as the administrative duties peculiar to garrison life. Japan itself consumed much of the off-duty time of the Redlegs. Passes enabled the men to become acquainted with the customs and the way of life of the people of the northernmost Japanese island with the aim of giving the men a clearer understanding of their coming role a guest of a friendly foreign nation.

Garrison duty lasted until September 20, 1952, when the 99th Field Artillery Battalion was again alerted for an amphibious move. The 99th loaded on the all too familiar amphibious craft at Otaru with rumors that the 8th Regimental Combat Team was again returning to the “Land of the Morning Calm”. The word was finally released that the 8th RCT would make a landing on the Korean shores, but only as a feinting move. This operation was appropriately called Operation FEINT. A practice landing was made at Kangnung below the 38th Parallel, after which the troops re-loaded and the task force steamed toward the North Korean harbor of Wonsan, where a show of strength was displayed to draw Red troops to that sector. The mission was a success and heavy Communist reinforcements were shifted to meet the feint. The convoy then steamed south and landed the 8th RCT at the harbor of Pohang-dong, where the Cav had landed on its previous trip to Korea.

The 99th Field Artillery debarked and traveled south to Inchon-ni, north of Pusan, where the Redlegs started erecting a base camp. Duties an Inchon-ni consisted mostly of building the camp area, improving the grounds and living area and general maintenance. Recreation included all types of sports and some pleasant hunting.

The Redlegs received orders sending them back to Japan and on the December 14, 1952, the 99th Field Artillery Battalion left its camp bound for Camp Crawford, Sapporo, Japan on Hokkaido.

Garrison Duty on Hokkaido

Once settled at Camp Crawford, the 99th Field Artillery Battalion began a series of intensive training cycles aimed at keeping the unit at top efficiency. The early winter months of 1953 found the Battalion participating in cold weather exercises patterned to train and test the unit in flexibility and mobility during adverse weather conditions. Under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Arthur J. Read, preparations were begun for a series of competitive tests designed to measure efficiency and combat readiness at various levels. The excellent results of the intensive training were first shown on 15 June, when “C” Battery, commanded by 1st Lieutenant Thurston Mason, distinguished itself as the best firing battery in Division Artillery. The Battery obtained an over-all score of 92.5 out of a possible 100.

Training progressed steadily throughout the spring and summer months. Emphasis was placed on the forthcoming competitive Artillery Battalion Tests, although many hours were also spent on combined Infantry and Artillery exercises. Weekly firing practice increased the long hours of field training and maintained a high degree of combat readiness.

As the summer grew to a close, preparations were made for a short period of rest and recuperation for the 99th Field Artillery Battalion. On August 22, the outfit, with their guns and section equipment headed to the shores of Lake Shikotsuko. While bivouaced at the Division “Rod and Reel” area, fishing, swimming, and other forms of recreation were integrated into the special training program.

On September 14, 1953, Lieutenant Colonel Arley L. Outland assumed command of the 99th replacing Major Charles H. Knecht, who had led the Redlegs since 13 May. Under LTC Outland’s command. the 99th adopted the title, “The Shootin 99th”. The title was highly upheld when, on 10 November, the Battalion once again distinguished itself by obtaining the highest Battalion Test score in Division Artillery.

Although fall was just around the corner and the cold winds began to fill the air, the unending tasks of a well trained Artillery battalion continued to mount. Dry net amphibious training under supervision of the Marines and air transportability training had both been an integral part of the overall training program. With preparations for an amphibious move having been planned for months in advance, the 99th Field Artillery Battalion as part of the 8th Regimental Combat Team, left Camp Crawford on November 8, for the move to Chikasaki Beach, just south of Yokohama. The main body of the Battalion moved on LST’s from Otaru on the same date with the remainder embarking on troop ships three days later. All ships arrived near the beach on 13 November. Amidst high winds and cold rain, a practice landing was made the next day with a similar performance the following day. On 16 November, all troops having been returned to their ships, the return trip was begun. The last troops reached Camp Crawford on 23 November amidst a heavy snowfall.

One big event remained for the 99th Field Artillery before the year’s activities ended. On 8 December, their guns rolled to the field to play their part in direct support of the 8th Cavalry Regimental Combat Team in their RCT Test. The Battalion distinguished itself with an “Excellent” rating.

Movement to Camp Younghans

In 1954, the Battalion continued its cycle of training and maintaining combat readiness. On September 26, 1954, 36 members of the Division Artillery advance party, mostly from the 99th, being sent south to set up a new duty station at Camp Younghans, near Sendai on Honshu, boarded the Japanese train ferry, Tōya Maru. The four and a half hour ferry ride to Aomori, Honshu was to be the first leg of the trip for them. From Honshu they were to load on LST’s and travel further south to Sendai and then drive the 40 miles to Younghans.

Typhoon No. 15, Marie, was in the Sea of Japan proceeding northeast towards the Tsugaur Strait. The Tōya Maru’s departure was delayed because another ferry, of inferior quality, was unable to depart due to weather, and its passengers and cars were transferred to the Tōya Maru. The captain of the Tōya Maru decided to cancel his journey at 1510 hours. Believing that the typhoon had passed by as predicted when the weather cleared and the outlook improved the captain changed his mind unaware that atypically, the typhoon had gained strength in the Sea of Japan.

At 18:39, the Tōya Maru departed from Hakodate with approximately 1,300 passengers aboard. Shortly thereafter, the wind picked up coming from a SSE direction.

At 19:01, the Tōya Maru lowered its anchor near Hakodate Port to wait for the weather to clear up again. However, due to high winds, the anchor did not hold and Tōya Maru was cast adrift. Water entered the engine room due to the poor design of the vehicle decks, causing its steam engine to stop and the Tōya Maru to become uncontrollable. The captain decided to beach the sea liner onto Nanae Beach, on the outskirts of Hakodate.

At 22:26, the Tōya Maru beached and an SOS call was made. However, the waves were so strong that the sea liner could no longer remain upright and at around 22:43, the Tōya Maru capsized and sank at sea several hundred meters off the shore of Hakodate. Of the 1,309 on board, only 150 people survived, while 1,159 (1,041 passengers, 73 crew and 41 others) died.

Among those killed were 35 American Soldiers from the 1st Cavalry Division Artillery who were traveling from Hokkaidō as an advance party to set up a new camp (Camp Younghans) near Sendai. One Soldier, Private First Class Francis P. Goedken, survived by escaping through a port hole. 2nd Lieutenant George A. Vaillancourt, Battery “C”, 99th Field Artillery Battalion, was posthumously awarded the Soldier’s Medal, the highest non-combat medal at the time, for his courage during the tragedy. The football field at Camp Younghans was dedicated to Lieutenant Vaillancourt on September 24, 1955.

After completing the move of the Battalion to Camp Younghans training continued. On 29 August 1957, compliance with a treaty, signed by the governments of Japan and the United States in 1957 which required the removal of all US ground forces from Japan’s main islands, went into effect. The 1st Cavalry Division, headquartered at Camp Drake, Tokyo along with its subordinate units stationed throughout Honshu, Japan, were given orders to reduce strength to zero personnel and transfer to Korea (minus equipment). On 23 September 1957, General Order 89 announced the redesignation of the 24th Infantry Division as the 1st Cavalry Division and issued orders to reorganize the Division under the “Pentomic” concept, which utilized five “Battle Group” maneuvering units, rather than the “regimental” units.

The 99th Field Artillery Battalion was inactivated on October 15, 1957 in Japan.

Taken from A History of the 99th Field Artillery Battalion provided to us by SSG Jim Miller who served with the 99th in Japan and during the Korean War and had obtained a copy from MAJ Darwin Palmer (deceased) who served with the 99th Field Artillery Battalion during World War II. Additional information gathered from Internet sources and an article written by SP-3 Peter O’Brien who served with the 61st FA in Japan.